The Godfather turns golden

Wednesday, March 30, 2022

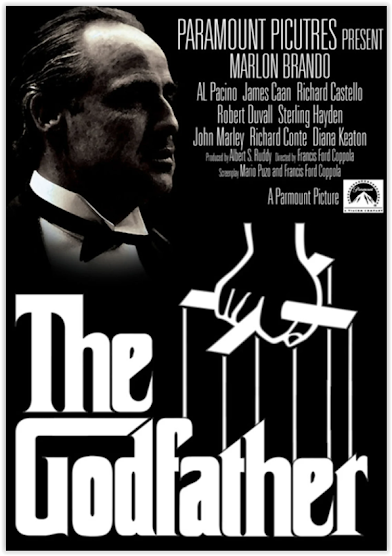

What can possibly be said or written about The Godfather that hasn’t already been expressed by countless film scholars, critics, and historians? Not much new, although it’s constructive to summarize what we already know and love about this ever-fresh cinematic treasure that marks a 50th anniversary this month. Here’s some food for thought to digest that, while it may not be as delicious as authentic Italian cuisine, may satiate your hunger for knowledge about Francis Ford Coppola’s supreme achievement, initially released in March 1972 (to listen to our Cineversary podcast spotlighting The Godfather, click here).

Why is this movie worth celebrating 50 years later? Why does it still matter, and how has it stood the test of time?

- The Godfather is worth celebrating because it stands undiminished five decades on as a cinematic testament to the power of myth and the evergreen quality of compelling storytelling. The narrative here is never less than captivating. The people who inhabit this story and what they represent are endlessly intriguing. And the mythos behind the Corleone family and the satellite characters in this tale continue to fuel the imagination.

- It also still matters because it provides a rare and detailed view of a private and privileged world that the vast majority of us will never encounter—a domain that is fabricated, sure, yet firmly grounded in reality and one that is intimate, personal, domestic, morally compromised, and, most fascinatingly, above the law.

- Coppola said in an interview: “People love to read about an organization that’s really going to take care of us…When the courts fail you and the whole American system fails you, you can go to Don Corleone and get justice.”

- It has stood the test of time because, despite their sins, we care about these characters and we’re invested in this underworld universe.

- According to Roger Ebert: “The Godfather is told entirely within a closed world. That’s why we sympathize with characters who are essentially evil...Don Vito Corleone emerges as a sympathetic and even admirable character; during the entire film, this lifelong professional criminal does nothing of which we can really disapprove…During the movie we see not a single actual civilian victim of organized crime. No women trapped into prostitution. No lives wrecked by gambling. No victims of theft, fraud or protection rackets. The only police officer with a significant speaking role is corrupt…The story views the Mafia from the inside. That is its secret, its charm, its spell.”

How was The Godfather innovative or different, especially compared to previous Hollywood crime/gangster pictures?

- Although some argue that The Godfather still romanticizes gangster culture and the wise guy way of life, it depicted the Italian American family and experience more realistically, in no small part because the studio selected an Italian American well versed in this culture to direct, and the film cast Italian Americans in crucial roles.

- In classic Hollywood gangster movies, non-Italian Americans often played stereotypical gangster characters with Al Capone-like qualities and over-the-top bravado, including Edward G. Robinson, Paul Muni, and James Cagney.

- Tom Santopietro, author of the book The Godfather effect, noted: “The vast majority of Italians have come to accept and actually embrace the film because I think the genius of the film, besides the fact that it is so beautifully shot and edited, is that these are mobsters doing terrible things, but permeating all of it is the sense of family and the sense of love… I think it squashed the idea that Italians were uneducated and that Italians all spoke with heavy accents… These were mobsters, but these were fully developed, real human beings. These were not the organ grinder with his monkey or a completely illiterate gangster…In films like Scarface [1932], the Italians are presented almost like creatures from another planet. They are so exotic and speak so terribly and wear such awful clothes. The Godfather showed that is not the case.”

- Note that the Italian-American Civil Rights League gave its blessing to the screenplay.

- Unlike gangster films made in the censorship era, the characters in The Godfather didn’t necessarily have to suffer a comeuppance or be brought to justice as a moral message. While many of these mobster personalities end up being killed or diminished, it is due to the actions of fellow gangsters who merit their own form of justice and retribution—not the criminal justice system.

- Additionally, The Godfather’s goombahs are much more psychologically multifaceted and benefit from greater character development than many mobsters depicted in prior films, including two immediate predecessors, 1968’s The Brotherhood and 1969’s The Italian Job.

- The Godfather also proved that mob movies could generate huge business and acclaim. It was the box office champ of 1972 and briefly was the largest grossing picture in history. It earned 10 Academy Award nominations, winning three, including Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actor for Marlon Brando. It also placed #2 on the American Film Institute’s 2007 list of the 100 greatest films of all time.

In what ways was The Godfather influential on cinema or popular culture?

- For better or worse, since the release of The Godfather in 1972, more than four in five Hollywood movies that have portrayed Italian Americans or Italian culture are “mob movies,” per the Italic Institute of America. Before The Godfather, that ratio was less than one in five.

- A host of films about the mafia and gangsters came in its wake, among them Mean Streets, Scarface, Once Upon a Time in America, The Untouchables, Goodfellas, Casino, Donnie Brasco, Gangs of New York, and The Irishman. And, of course, the TV show The Sopranos is a direct descendant of The Godfather (and Goodfellas).

- Before The Exorcist, Jaws, or Star Wars, The Godfather was the first blockbuster of the New Hollywood era that would be dominated by young filmmakers like Coppola, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg, raking in massive dollars and serving as one of the first must-see event movies, of which there were several in the 1970s and beyond.

- With its cynical tone, pessimistic vibe, and violent imagery, The Godfather continued a trend in American cinema in the early 1970s of telling dark, unsettling stories that mirrored the negative emotional undercurrent of the times, when the American public was focused on the Vietnam War, the fall of the counterculture, the fresh news of Watergate, and mistrust in the government.

- The violence in The Godfather, much of which is disturbing and grotesque, especially for 1972, would have been less acceptable in a lesser film. We are shown a bloody horse head, a beaten pregnant woman, two grotesque deaths by strangulation, a gunshot to the eye, point-blank killings of two men via gunshots to the head, and the gruesome murders of several mob bosses. Five years after Bonnie and Clyde and three years following The Wild Bunch, Coppola and his team take graphic violence in a mainstream movie to a new extreme.

- The Godfather set a new template for quality in film franchises, creating high expectations for its follow-ups. The Godfather II knocked it out of the park and is debatably even better than the original, possibly standing as the greatest sequel ever made.

- This picture jumpstarted the careers of Coppola, Pacino, Keaton, Cazale and gave a second life to Brando’s faltering career.

- Before the Godfather, epic films with a long runtime had an intermission; this movie broke that trend.

- Arguably, The Godfather made the mafia lifestyle look more appealing to the mainstream, possibly motivating some to get involved in organized crime.

- One mark of its enduring popularity is the extent to which the film has been parodied and spoofed innumerable times in movies and TV shows, from Saturday Nite Live and SCTV to The Simpsons, South Park, and Family Guy to The Freshman co-starring Brando.

What themes, messages, or morals are explored in The Godfather?

- The corrupting nature of power and how clout, control, and influence are more important than family.

- The death of the American dream at the hands of capitalistic ambition. Recall the opening words of the film: “I believe in America.” But…

- In his excellent recent writeup published at Deepfocusreview.com, Brian Eggert wrote: “The Godfather dramatizes how the American Dream has failed, leaving only raw capitalism, epitomized by the brutality of the Corleones under Michael. If the family under Don Vito represents the fantasy of having the power to enforce the American Dream, criminally achieved though it may be, the family under Michael sacrifices familial solidarity for corporate greed and stability. Don Vito understood the criminal enterprise served the family, which must be protected and appreciated. Michael turns the family business from a mom-and-pop shop to a corporation bent on mergers and acquisitions—not unlike Gulf+Western, the conglomerate that purchased Paramount in 1966. The film in Coppola’s hands, then, reveals that the dog-eat-dog nature of American capitalism has literally closed the door on the family. Coppola shows this twice: first when Michael shuts the phone booth door on Kay, who must stand in the cold outside while he learns of the attempted assassination on his father; second, in the famous final shot, when Michael’s office door shuts on Kay, creating a permanent barrier between the two. The film shows that not even the Corleone family can survive capitalist greed. The family unit endures, to be sure. But it’s at the cost of love, trust, and everything that made the family so appealing under the rule of Don Vito.”

- Familial succession. Like King Lear, this is a tale about a patriarch with three sons, one of whom will fill his father’s shoes when he steps down.

- The outsider becomes the insider. Early in the film, Michael tells Kay how he is different from his family. He has served in World War II and gone to college and appears to be on a path that will diverge from his father and brothers. He is not part of Vito’s inner circle nor as close to his parents or siblings as you would expect the youngest son to be. But that all changes once he learns of Vito’s near-killing, at which point Michael rushes to his father’s side and embraces the darkness and vices surrounding the Corleone family business. He quickly becomes an insider and earns the trust of his dad, who ultimately bequeaths his power to Michael.

- Old World ways vs. New World tactics. Vito exemplifies the former, Michael the latter. In being forced to hide in Sicily, his father’s birthplace, Michael comes to embrace Old World ways and thinking, even marrying a native girl. But when she is violently killed and his bodyguard betrays him, he returns to America a further changed man. Now in command, he abandons his father’s Old World approach to running the family business and adopts his own cold, ruthless, and efficient American methodology, which will involve violating the old school mobster code of conduct by killing family members and wiping out his business enemies—even though Vito had attempted to make peace with the other four mob families. Michael famously tells Sonny, “It’s not personal…it’s strictly business.” But the truth is that, for Michael, it's both: By privately taking these matters personally, Michael can destroy his adversaries who abide by Old World mafia ethics and become more powerful and successful.

- Selling your soul for success and sway. The genius baptism scene, with crosscutting lines of action in which Michael’s henchmen wipe out his rivals and betrayers while Michael stands before a priest in a church and verbally agrees to renounce Satan and all his works and promises, underscores an important message: that each of us faces a constant choice between the sacred and the profane, between fidelity and treachery, between love and hate.

- The importance of allegiance and reliability. Ebert wrote: “Much is said in the movie about trusting a man’s word, but honesty is nothing compared to loyalty.”

- Appearances can be deceiving.

- Even though he looks weakened after the assassination attempt on his life, Vito Corleone demonstrates his cunning and powers of perception by choosing Michael as his successor and advising him on who to trust and not trust.

- At first glance, Michael appears to be a laid-back, introverted, laconic, and deferential individual; he’s younger and more diminutive than his brothers and even shorter than Kay. But we learn how strong-willed, devious, commanding, and explosive he can be, regardless of his physical stature or younger age.

- As the eldest, most verbose, tallest, and debatably most handsome son, Sonny would seem to be the ideal heir to his father’s throne, but we soon see how his volatile nature handicaps his judgment and leads to his demise.

- We discover, as Michael does, that many characters we didn’t necessarily suspect end up betraying the Corleone family, including Tessio, Carlo, Barzini, Paulie, and one of Michael’s bodyguards in Sicily.

- Even the movie’s title is deceptive because one would think the story is named after Vito when it could instead be a reference to the other godfather, Michael, who dominates the second half of the tale.

Why was Francis Ford Coppola the ideal director for The Godfather? What special qualities does he bring to the film?

- Coppola deserves substantial credit for his uncompromising vision and stalwart belief in the actors, setting, story. He insisted on casting Pacino and Brando and keeping the setting consistent with the novel: the 1940s through 1950s.

- He knew and lived the Italian American experience and understood the family dynamics.

- Coppola brilliantly weaves themes of the corrupting influence of power and money at the expense of family unity, paring back many other subplots and situations found in Mario Puzo’s novel and focusing more on family ties and ancestral rites of passage in the movie. Consider that the pivotal events in the picture center around a handful of key family gatherings and religious rituals: there are two weddings, a baptism, and a funeral.

- The way Coppola introduces these players and sets up the interrelationships and familial power structure within the first 30 minutes, during the wedding extended sequence, is like a masterclass in filmmaking, cutting between the dark internal shots of Vito in his office and the multitude of relatives and friends celebrating in the sun-drenched yard outside.

- Interestingly, Coppola consistently utilizes slow dissolves between scenes to create a dreamlike quality.

What is The Godfather’s greatest gift to viewers?

- One of The Godfather’s greatest gifts is that, like the concept of a perpetual motion machine that defies the laws of physics and logic, it never ages. Fifty years have only elevated the stature of what long ago was already considered an exceptional and eternally memorable motion picture thanks to two particular facets: unforgettable scenes and set pieces as well as infinitely quotable lines that have become sacrosanct in pop culture. Brando’s recitation of the film’s most famous line, “I’m going to make him an offer he can’t refuse,” forever brings nostalgic joy to the repeat viewer, regardless of its nefarious true meaning; we can never unsee that decapitated horse head or unhear the screams of Jack Woltz discovering that head; wrapped fish have taken on a whole new connotation since 1972; Michael’s tense meeting with Sollozzo and the police captain will always enthrall; after witnessing how meticulous Clemenza is with culinary matters, as he is with the minutia required of a well-planned murder, we can appreciate why cannoli is worth saving, even if we’ve never actually tasted this Italian confection; and the film’s concluding baptism montage juxtaposing a holy rite with shrewdly orchestrated acts of carnage, set to some downright eerie church organ music and superbly edited, is legend-making stuff that continues to demonstrate why Coppola was probably the finest American filmmaker of the 1970s.

- Another greatest gift is the scintillating cinematography of Gordon Willis. He immediately establishes the dark emotional milieu of this Cosa Nostra epic with his dimly lit, darkly furnished Corleone office, the perfect lair for backroom dirty-dealing and king-making. He contrasts the deep browns and engulfing blacks of Vito’s restricted sanctum with the sun-saturated outdoor shots of the wedding to create a visually and emotionally contrasting lighting palette. And Willis shows throughout the film, with moderately to predominantly dark compositions, how shades of doubt, fear, anger, and weariness can engulf one or more characters.