A cinematic game of Clue

Monday, July 25, 2022

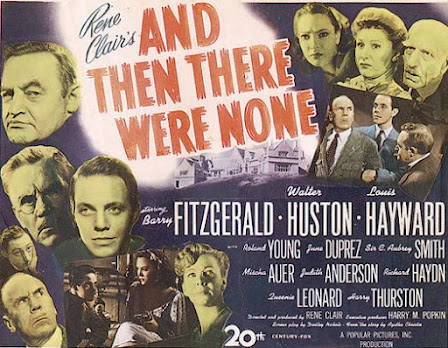

Nobody dunnit better than everybody’s favorite whodunnit author Agatha Christie. And no book of hers was as popular, based on sales (over 100 million claimed), as And Then There Were None (also known as Ten Little Indians), which was adapted for the big and small screen numerous times. Yet the version that probably remains the most beloved among film critics and scholars is the 1945 production directed by René Clair. Our CineVerse club played the role of movie detective last week when we attempted to examine the clues that point to quality filmmaking at work in this picture. Here’s a recap of our conversation (to listen to a recording of our group discussion, click here).

What was noteworthy, memorable, unforeseen, or enjoyable about this movie?

- The filmmakers changed Christie’s original ending, in which (SPOILERS) everyone dies and UN Owen commits suicide, for a more cheerful conclusion featuring two young survivors who discover romance.

- The ensemble cast includes an impressive array of fantastic character actors and former leading stars, including Walter Huston, Barry Fitzgerald, Roland Young, Judith Anderson, C. Aubrey Smith, and Richard Haydn. Including familiar and beloved faces like these helps create a rich tapestry of delightful performances.

- It employs Hitchcockian black comedy, such as when the shoes of Thomas Rogers, the dead male servant, are revealed, as well as comic relief in the form of Mischa Auer’s Prince Nikita and Richard Haydn’s Rogers.

- The players break the fourth wall by looking directly at the audience, a practice sometimes used in theater performances, particularly in mysteries where the director wants the crowd to suspect or remember that character.

- While it’s obvious to see how this would have been a popular stage play, the director and his collaborators use the power of film and editing to expand the narrative beyond the confining handful of rooms in which the events occur.

- TCM reviewer Jeremy Arnold wrote: “The most impressive thing about And Then There Were None is how cinematic it feels. While it's true that the screen credits say the script is based on Christie's novel, the ending comes from her stage version, and the entire concept of ten people trapped in one space trying to puzzle through a mystery primarily via dialogue is at heart a theatrical conceit. Yet Nichols' script finds fluid ways of moving the action fairly constantly to different locations around the house or on the island, and director Clair uses ingenious methods of breaking up the space cinematically in scenes that do linger in one specific space. For example, if several people are gathered in a room or hallway for several minutes, talking, Clair will use deft editing to create tension or humor and make the scene feel anything but stagy. This is very tricky business, as Clair is not cutting on action so much as using editing to create action, and turning theatrical space into cinematic space. Even though the film is not technically adapted from a play, it is still a model of how to make such an adaptation and should be studied by any filmmaker doing so today.”

Major themes, motifs, and tropes

- Captive characters: The players in these tales are often trapped, sequestered, or cut off from the outside world

- Darkness and shadows: Shades of black and grey engulf the characters and obscure identities and facts for the audience

- Whodunnits: The viewer is dependent on learning the facts and deciding who the antagonist is, often by process of character elimination.

- Fiendishly clever crimes: The murderer in this tale kills his victims in keeping with the lyrics of a song, Ten Little Indians.

- Red herrings: It’s important in old dark house mysteries for the filmmakers to mislead the viewer and throw the audience off the true scent by suggesting a character’s guilt or participation in foul play, only for us later to learn that we were deceived.

- There’s strength in numbers, usually: By sticking together and forming alliances, some of the 10 characters avoid being killed; nevertheless, the doctor meets his doom despite teaming up with the judge.

Similar works

- Subsequent adaptations of this tale, including film and TV versions from 1965, 1974, 1987, 1989, 2015, and 2020.

- Old dark house subgenre films like The Cat and the Canary (1927 and 1939), The Old Dark House, The Ghost Breakers, Clue, Murder By Death, House on Haunted Hill, and The House of Fear

- Thrillers in which the villain dispenses with his victims in diabolically crafty ways meant to merit out poetic justice, such as Theater of Blood, or conform to a myth, song, or work of literature, such as Seven or The Abominable Dr. Phibes

- Incite Mill

- Twitch of the Death Nerve

- John Carpenter’s The Thing

- The Trouble With Harry

Other films by René Clair

- The Ghost Goes West

- I Married a Witch

- It Happened Tomorrow

- Beauty and the Devil

- Beauties of the Night