Parallax to the max

Wednesday, June 28, 2023

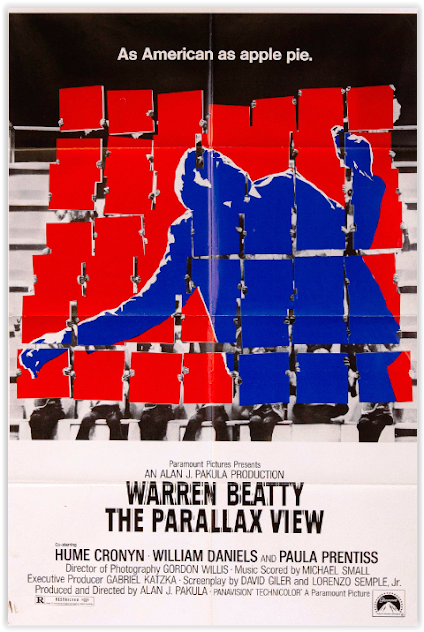

Directed by Alan J. Pakula and produced by/starring Warren Beatty, The Parallax View emerged as a captivating political thriller in 1974. The narrative follows Joseph Frady, an intrepid reporter (Beatty), as he embarks on an investigation into a series of enigmatic deaths associated with the clandestine Parallax Corporation. Frady's pursuit unveils a perilous network of political intrigue and secrecy.

Regarded as a classic in the conspiracy thriller genre, The Parallax View delves into themes of government corruption, assassination, and the manipulation of public perception. The film benefits from the stylish guidance of Pakula, who adeptly weaves a web of tension and paranoia throughout the story. The cinematography, editing, and skillful use of visual symbolism further contribute to its lasting impact. Among its standout sequences, this movie showcases an iconic and unforgettable “carousel scene,” which occurs at a political rally staged within a domed carousel, enveloping viewers in suspense.

Regarded as a classic in the conspiracy thriller genre, The Parallax View delves into themes of government corruption, assassination, and the manipulation of public perception. The film benefits from the stylish guidance of Pakula, who adeptly weaves a web of tension and paranoia throughout the story. The cinematography, editing, and skillful use of visual symbolism further contribute to its lasting impact. Among its standout sequences, this movie showcases an iconic and unforgettable “carousel scene,” which occurs at a political rally staged within a domed carousel, enveloping viewers in suspense.

Click here to listen to a recording of our group discussion of The Parallax View, conducted last week.

Why would have audiences connected well with this film upon its release in 1974? How would it have captured the zeitgeist of the times? Americans were growing more suspicious of authority and distrustful of government in the wake of Watergate, the Vietnam War, the Warren Commission findings, and the assassinations of major leaders. The movie drew upon the collective memory of significant assassinations in the 1960s, such as those of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. These high-profile events had already fostered an atmosphere of suspicion and conspiracy theories in society. The Parallax View capitalized on this existing sentiment, presenting a chilling narrative that delved into political assassinations and the subsequent cover-ups.

Indeed, there was a pervading, brooding sense of paranoia and cynicism in the culture, and conspiracy theories were becoming more popular to explain political mysteries.

The Parallax View also effectively tapped into the tense atmosphere of the Cold War era, where the fear of communist infiltration and suspicions of covert government activities were widespread. Audiences were already preoccupied with the notion of hidden forces at play, and the film skillfully played into those concerns by exploring the concept of a secretive, powerful organization with its own hidden agenda. Consider that many Americans felt helpless to affect change and ignorant of what might really be going on.

Lastly, remember that the 1970s was the golden age of the political/paranoia/assassination thriller, and this was regarded among the best of that subgenre.

Filmmaking elements that make this movie so effective include superb compositions that frame subjects in a way to evoke a feeling of powerlessness and isolation and advance the mood. Recall the use of long shots and extreme long shots that show a character as vulnerable, alienated, and lost in their surroundings; yet, despite being so far away visually from the subject, we can hear them as if they were close by. Pakula and company employ vast empty spaces to progress this emotion of feeling dislocated and alone; close-ups are used sparingly.

A distinctively dark visual style is emphasized, too. Consider that cinematographer Gordon Willis is responsible for all the Godfather movies, eight Woody Allen films, and three Pakula films; he was known as “the prince of darkness” for his reliance on shadows and often preventing a character’s eyes from being seen clearly. Occasionally, Willis utilizes shallow focus that reveals a blurred, shadowy, mysterious environment surrounding the protagonist.

Moreover, this film uses brilliant editing to pace the building tension, including a bold use of Soviet montage-style editing during the training video. The montage theory posits that otherwise normal images that are juxtaposed with unrelated images take on a whole new meaning due to new associations the viewer makes with the image before it and after it.

Also particularly impactful is the shrewd use of sound effects and sound editing in The Parallax View, which forces you to pay attention to the small aural details.

What’s interesting about the narrative and POV in this movie is how the first half unfolds in a conventional narrative style, but the second half leaves you feeling more unsure about everything. In the first half, the audience is more omniscient than the hero; but after the midway point, we’re not as informed as Frady.

This is a movie that also plays with the audience. Like Hitchcock’s Psycho, we learn that most of the narrative has potentially been a red herring meant to mislead.

Finally, storywise, the movie doesn’t dumb down or fall into clichés. There is no romantic subplot or obligatory sex scene, and no overacting by Beatty. His character treats the threat as something real and probable, not a fantastical cartoonish villain.

Read more...

Indeed, there was a pervading, brooding sense of paranoia and cynicism in the culture, and conspiracy theories were becoming more popular to explain political mysteries.

The Parallax View also effectively tapped into the tense atmosphere of the Cold War era, where the fear of communist infiltration and suspicions of covert government activities were widespread. Audiences were already preoccupied with the notion of hidden forces at play, and the film skillfully played into those concerns by exploring the concept of a secretive, powerful organization with its own hidden agenda. Consider that many Americans felt helpless to affect change and ignorant of what might really be going on.

Lastly, remember that the 1970s was the golden age of the political/paranoia/assassination thriller, and this was regarded among the best of that subgenre.

Filmmaking elements that make this movie so effective include superb compositions that frame subjects in a way to evoke a feeling of powerlessness and isolation and advance the mood. Recall the use of long shots and extreme long shots that show a character as vulnerable, alienated, and lost in their surroundings; yet, despite being so far away visually from the subject, we can hear them as if they were close by. Pakula and company employ vast empty spaces to progress this emotion of feeling dislocated and alone; close-ups are used sparingly.

A distinctively dark visual style is emphasized, too. Consider that cinematographer Gordon Willis is responsible for all the Godfather movies, eight Woody Allen films, and three Pakula films; he was known as “the prince of darkness” for his reliance on shadows and often preventing a character’s eyes from being seen clearly. Occasionally, Willis utilizes shallow focus that reveals a blurred, shadowy, mysterious environment surrounding the protagonist.

Moreover, this film uses brilliant editing to pace the building tension, including a bold use of Soviet montage-style editing during the training video. The montage theory posits that otherwise normal images that are juxtaposed with unrelated images take on a whole new meaning due to new associations the viewer makes with the image before it and after it.

Also particularly impactful is the shrewd use of sound effects and sound editing in The Parallax View, which forces you to pay attention to the small aural details.

What’s interesting about the narrative and POV in this movie is how the first half unfolds in a conventional narrative style, but the second half leaves you feeling more unsure about everything. In the first half, the audience is more omniscient than the hero; but after the midway point, we’re not as informed as Frady.

This is a movie that also plays with the audience. Like Hitchcock’s Psycho, we learn that most of the narrative has potentially been a red herring meant to mislead.

Finally, storywise, the movie doesn’t dumb down or fall into clichés. There is no romantic subplot or obligatory sex scene, and no overacting by Beatty. His character treats the threat as something real and probable, not a fantastical cartoonish villain.

Similar works

- Hitchcock's Foreign Correspondent, Notorious, The Man Who Knew Too Much, North by Northwest

- John Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and 7 Days in May (1964)

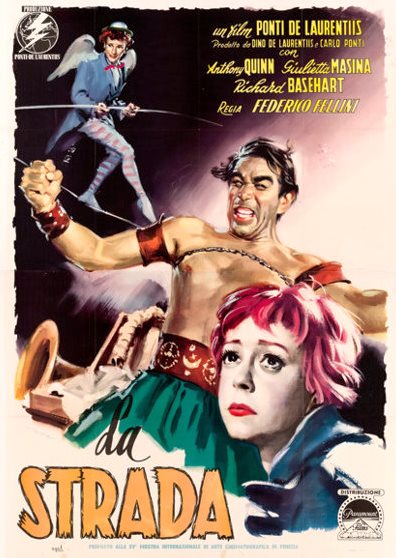

- European works like The Battle of Algiers (1964), Z (1969), and Day of the Jackal (1973)

- Other political action thrillers, including:

- Executive Action (1973)

- Day of the Dolphin (1973)

- Chinatown (1974)

- The Conversation (1974)

- Three Days of the Condor (1975)

- All the President’s Men (1976)

- Capricorn One (1977)

- Winter Kills (1979)

- Blow Out (1981)

- Missing (1982)

- No Way Out (1986)

- JFK (1991)

Other films by Alan J. Pakula

- Klute

- All the President’s Men

- Sophie’s Choice

- Presumed Innocent

- The Pelican Brief