The Queen comes clean

Wednesday, November 29, 2023

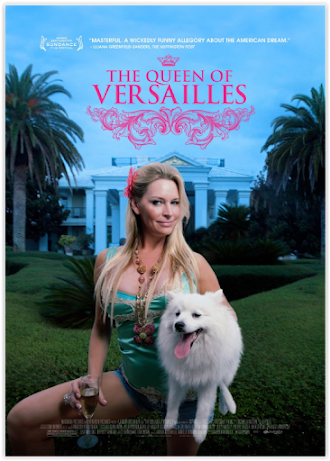

Director Lauren Greenfield hit the documentary jackpot when she was filming The Queen of Versailles, her 2012 feature chronicling the lives of uber-rich couple David and Jackie Siegel. That’s because the 2008 financial meltdown happened during production, which seriously threatened the fortunes of Siegel and his timeshare empire, transforming the film seemingly from a puff piece profile of extravagant prosperity to a cautionary tale rumination on the fleeting nature of wealth and privilege. The timing was perfect, as the Siegels were constructing the largest single-family home in the United States, inspired by the Palace of Versailles in France, while the cameras were rolling, until the financial crisis hit and their Xanadu was put on hold. This doc adeptly captures the aftermath of that tumultuous period, providing a distinctive perspective on how economic downturns can impact even the most advantaged individuals. David and Jackie Siegel emerge as fascinating—if not completely unsympathetic—characters, shedding light on the extravagances and vulnerabilities inherent in the lives of the super-rich. The Queen of Versailles also serves as a timely social commentary on opulence, consumerism, and the pursuit of the American Dream, prompting watchers to ponder the ramifications of unbridled ambition and materialism.

To listen to a recording of our CineVerse group’s discussion of this film, conducted last week, click here.

Unparalleled access to privileged lives makes this movie particularly riveting. It’s easy to question why David and Jackie would allow the cameras to infiltrate into their present and past lives to such an intimate and revealing extent. And some of the unflattering, nakedly candid, and boastful things David says are eyebrow-raising – things he will likely later regret revealing.

It’s difficult to feel sorry for these real-life characters whatsoever, considering their extravagant lifestyles, selfish proclivities, and swaggering attitudes. But Jackie in particular can sometimes evoke our empathy – not necessarily sympathy – because she appears more down-to-earth, humanistic, and centered than her husband.

The filmmakers seem to be relatively objective and fair-handed in the footage they present, avoiding any statement-making about, for example, David’s financial comeuppance. However, a New York Times article brought the director’s editing approaches into question, suggesting that shots were arranged out of order to affect the narrative timeline, which suggests that this film is biased and manipulative. Reviewer Brian Orndorf wrote: “Greenfield keeps the focus on the absurdity of behavior and routine, studying David and Jackie for cracks in their veneer, hoping to expose a pinhole of vulnerability as the empire comes crashing down around them, introducing new realities for the pair and their kids, a spoiled yet observant bunch who will have to sing for their supper when adulthood hits them like a truck.”

Major themes woven into this work include the dark side of the American dream, hubris, bad karma, and schadenfreude. David Siegel is easy to dislike because he comes across as arrogant, boastful, narcissistic, and opportunistic. His fall from financial heights is especially delicious to viewers who find him vulgar and appalling in his ostentatious lifestyle. Indeed, The Queen of Versailles also reminds us that pride goeth before a fall. This story proves, yet again, that overconfident, self-important, and conceited people are likely to fail and suffer indignity and public scorn. The Economist wrote: “The film's great achievement is that it invites both compassion and Schadenfreude. What could have been merely a silly send-up manages to be a meditation on marriage and a metaphor for the fragility of fortunes, big and small.”

Life lesson #2? Never forget your roots. Jackie comes across as a slightly more relatable character we can empathize with, partially because she doesn’t forget where she came from and she demonstrates compassion and generosity for those less fortunate, although she is also spoiled, privileged, and presumptuous. Recall how she mistakenly thinks that the car rental company will provide a chauffeur and that the hired help can handle all of the responsibilities around her home.

The emperor wears no clothes is another clear takeaway. David and Jackie flaunted their wealth and power for years, but face a reckoning after the financial crisis of 2008. Despite having a home that appears lavish and countless enviable possessions, their property is littered with feces and accumulated junk – a symbol of how, despite being rich on paper, this couple has poor values.

Lastly, this is certainly a story of a floundering family tree. David and Jackie should be overjoyed that they have a large family and many children who, at least earlier in the story, presumably won’t have to worry about their financial futures. But they take these kids for granted, let other caregivers primarily raise them, and in the case of David show little to no attention. A man can, despite lacking money, be enriched with the rewarding responsibility of having a family, but David appears to be going broke on both fronts.

To listen to a recording of our CineVerse group’s discussion of this film, conducted last week, click here.

Unparalleled access to privileged lives makes this movie particularly riveting. It’s easy to question why David and Jackie would allow the cameras to infiltrate into their present and past lives to such an intimate and revealing extent. And some of the unflattering, nakedly candid, and boastful things David says are eyebrow-raising – things he will likely later regret revealing.

It’s difficult to feel sorry for these real-life characters whatsoever, considering their extravagant lifestyles, selfish proclivities, and swaggering attitudes. But Jackie in particular can sometimes evoke our empathy – not necessarily sympathy – because she appears more down-to-earth, humanistic, and centered than her husband.

The filmmakers seem to be relatively objective and fair-handed in the footage they present, avoiding any statement-making about, for example, David’s financial comeuppance. However, a New York Times article brought the director’s editing approaches into question, suggesting that shots were arranged out of order to affect the narrative timeline, which suggests that this film is biased and manipulative. Reviewer Brian Orndorf wrote: “Greenfield keeps the focus on the absurdity of behavior and routine, studying David and Jackie for cracks in their veneer, hoping to expose a pinhole of vulnerability as the empire comes crashing down around them, introducing new realities for the pair and their kids, a spoiled yet observant bunch who will have to sing for their supper when adulthood hits them like a truck.”

Major themes woven into this work include the dark side of the American dream, hubris, bad karma, and schadenfreude. David Siegel is easy to dislike because he comes across as arrogant, boastful, narcissistic, and opportunistic. His fall from financial heights is especially delicious to viewers who find him vulgar and appalling in his ostentatious lifestyle. Indeed, The Queen of Versailles also reminds us that pride goeth before a fall. This story proves, yet again, that overconfident, self-important, and conceited people are likely to fail and suffer indignity and public scorn. The Economist wrote: “The film's great achievement is that it invites both compassion and Schadenfreude. What could have been merely a silly send-up manages to be a meditation on marriage and a metaphor for the fragility of fortunes, big and small.”

Life lesson #2? Never forget your roots. Jackie comes across as a slightly more relatable character we can empathize with, partially because she doesn’t forget where she came from and she demonstrates compassion and generosity for those less fortunate, although she is also spoiled, privileged, and presumptuous. Recall how she mistakenly thinks that the car rental company will provide a chauffeur and that the hired help can handle all of the responsibilities around her home.

The emperor wears no clothes is another clear takeaway. David and Jackie flaunted their wealth and power for years, but face a reckoning after the financial crisis of 2008. Despite having a home that appears lavish and countless enviable possessions, their property is littered with feces and accumulated junk – a symbol of how, despite being rich on paper, this couple has poor values.

Lastly, this is certainly a story of a floundering family tree. David and Jackie should be overjoyed that they have a large family and many children who, at least earlier in the story, presumably won’t have to worry about their financial futures. But they take these kids for granted, let other caregivers primarily raise them, and in the case of David show little to no attention. A man can, despite lacking money, be enriched with the rewarding responsibility of having a family, but David appears to be going broke on both fronts.

Similar works

- Billionaire Boys Club

- The Big Short

- Too Big to Fail

- Some Kind of Heaven

- Inside Job

- Untouchable

- Reality TV series like The Real Housewives

Other films by Lauren Greenfield

- Thin

- Generation Wealth

- The Kingmaker