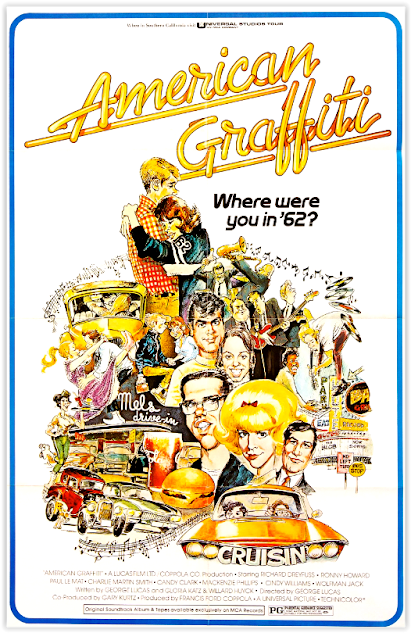

Fifty years ago, George Lucas hit one out of the park with American Graffiti, a comedy-drama film that serves as a memorable coming-of-age story. Set against the backdrop of the last night of summer vacation in 1962 in Modesto, California, the film follows a group of young individuals as they share their final evening together before embarking on separate journeys into college and adulthood.

The film boasts an ensemble cast and is renowned for its period piece details, its memorable soundtrack featuring iconic rock and roll tunes, and its exploration of themes related to youth, rebellion, and the inexorable march of time.

Premiering on August 11, 1973, American Graffiti achieved both critical acclaim and commercial success. It garnered multiple Academy Award nominations, including a Best Picture nod, and ultimately secured the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. The film's triumph played a pivotal role in shaping George Lucas's career, providing him with the resources and recognition necessary for the development of his subsequent project, Star Wars.

To listen to a recording of our CineVerse group discussion of this film conducted earlier this month, click here. To hear the latest Cineversary podcast episode marking the 50th anniversary of American Graffiti, click here. American Graffiti is deserving of commemoration five decades onward for numerous reasons—not the least of which is it’s an incredibly fun and entertaining work that balances comedy, romance, and light thrills with more serious underlying themes like the uneasy transition into adulthood, ambition versus comfort and complacency, fear of obsolescence, and more—evergreen messages that can transcend generations.

Long before the first Star Wars film, it’s a movie that proved George Lucas had real talent—maybe not so much as a director than as a storyteller with big ideas and a knack for innovating narratively and technologically, as he and his collaborators demonstrate in American Graffiti with its groundbreaking sound design and cross-cutting between four main characters, which was considered controversial at the time.

American Graffiti is among the most influential films ever made, especially when you consider its soundtrack, its heavily copied story template, and the way it helped fuel the 1950s nostalgia craze in the 1970s.

For a film depicting adolescents on the cusp of adulthood, it’s also the rare coming-of-age picture that isn’t heavily focused on teen rebellion or overtly critical of the establishment or older generations. This is primarily about kids having fun while also having to face difficult choices, but there are no serious conflicts. No one dies, gets arrested, protests authority, or delivers a teenage angst sermon.

American Graffiti is also worthy of respect and admiration because, even 50 years later, it serves as that rare example of a little film that became a huge cultural phenomenon on the strength of a fine script, excellent casting, good acting, great music, and zeitgeist luck. It’s one of the most profitable motion pictures ever made considering its meager initial budget, which reminds us that unlimited financial resources certainly don’t guarantee a work of lasting quality. In our current era of Hollywood bloat where sequels, remakes, superhero movies, and films tied to products and brands rule the roost—yielding diminishing box-office returns—it’s refreshing to remember that some of the best movies ever made were small productions lovingly crafted by talented mavericks and visionary filmmakers.

Getting back to that thespian troupe, it’s incredible to think that so many of these actors were relative unknowns back in 1973. American Graffiti catapulted the careers of Harrison Ford, Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard, Cindy Williams, Charles Martin Smith, Mackenzie Phillips, Paul Le Mat, Candy Clark, and Kathleen Quinlan. This is one of the most impressive young casts ever assembled.

This also remains a highly revered and critically acclaimed work, placing #62 on the AFI’s top 100 films list and garnering a 97% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

American Graffiti’s approach to music was pioneering. Using pop tunes in Hollywood films had been done before in works like The Graduate and Easy Rider. But perhaps taking a cue from Peter Bogdonovich’s The Last Picture Show two years earlier, Graffiti is that rare film that used popular period songs as diegetic music (heard by the characters in their world), with no traditional score or original music written for the film, with spectacular results. The early rock and roll tunes are perfectly chosen to accurately represent the late 1950s and early 1960s; like a Greek chorus of sorts, their lyrics are often used to comment on the mood, action, or character in that given scene. The vintage rock and roll music laced throughout American Graffiti serves as a character unto itself (Elvis's music is noticeably missing because they couldn’t afford the rights to his songs). This was one of the first soundtracks that became a blockbuster album, a trend that would continue with the Saturday Night Fever and Grease soundtracks later in the decade. The music becomes a character unto itself in this film.

Additionally, the sound design by Walter Murch moved the goalposts by demonstrating that you could make the music and audio effects sound three-dimensional and realistic within the universe the characters inhabit. Murch called this effect “worldizing,” and it involved not only creative editing but also blending a song’s original recording with a re-recorded take of that song played in a space where a character might hear it, such as within a school gymnasium. Murch also added aural directionality, echo, acoustic depth of field, and other effects to the sounds and songs, allowing us, for example, to hear what it might sound like in a passing car playing that music. Lucas said that he “used the absence of music, and sound effects, to create the drama.” The aural aesthetics in this film likely inspired the innovative sound designs in The Conversation, Nashville, Apocalypse Now, and other films of the 1970s and beyond.

American Graffiti also includes one of the most memorable postscripts (a text epilogue informing us what happens to one or more characters in the film) in movie history. We learn the fates of Curt, Steve, John, and Terry, one of whom will die soon, another who will go missing in Vietnam, and only one of whom escapes his hometown for a presumably bigger, better life. Famous postscripts were used previously in movies like A Man For All Seasons and Army of Shadows. Perhaps American Graffiti’s decision to use a postscript epilogue inspired the postscript endings for Barry Lyndon, All the President’s Men, Animal House (also set in 1962), and several other later films.

The popularity of American Graffiti was a strong catalyst for the 1950s revival trend that caught fire in the 1970s. In the wake of American Graffiti, the TV series Happy Days, Laverne & Shirley, and Sha Na Na got the green light, and several films depicting this era were released, including The Lords of Flatbush, Cooley High, American Hot Wax, The Buddy Holly Story, and the box office smash Grease. Wolfman Jack, a DJ synonymous with the early rock n roll era, also enjoyed a career boost. Later, other films set during a similar late 1950s/early 1960s period proved popular, including Diner, Stand By Me, Back to the Future, and Dirty Dancing.

American Graffiti can be credited for kicking off the nostalgia craze—a trend that continued in subsequent decades. Movies like Forrest Gump, That Thing You Do, Dazed and Confused, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Licorice Pizza, and Lady Bird, and TV series like That ’70s Show and The Goldbergs likely owe a debt to this work, which proved that audiences long to revisit bygone times from their younger years or yearn to be immersed in an interesting cultural era that may seem simpler, safer, and more enjoyable than our modern stressful times.

Little White Lies writer Daniel Allen

wrote: “Here (nostalgia) is a force explicitly deployed by Lucas – gazing back towards a specific period and the music, fashion, movies, and events that came from it. These tap into the fond memories and positive associations of those in the audience who lived through the era, using the viewer’s sentimental affection to bolster the film’s emotional impact. Nostalgia is such a potent tool because it is a form of escapism from aging or the bleak present. If you’re suddenly feeling rather old or unsettled by the modern world, why not watch a movie that captures your teenage years? It helps that the 1950s saw the arrival of popular culture as we know it – shaped by the youth and defined by film, television, celebrity, and music. The baby boomers were the first generation to benefit and American Graffiti became the first film to capitalize on their affection for their teenage years.”

This movie also contributed to the subgenre dubbed “one crazy night,” in which the events occur over a single day or evening. After American Graffiti, similar “one crazy night” narratives included Porky’s, After Hours, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Dazed and Confused, Can’t Hardly Wait, Superbad, Project X, and Booksmart.

As far as precedents, American Graffiti was inspired by Fellini’s I Vitelloni and has drawn comparison to other earlier works like 8½ (which also has a beautiful angelic muse character), The Last Picture Show (another period drama with characters stuck in a dead-end town), and The Wizard of Oz (which, like this film, features a magical “man behind the curtain”).

American Graffiti is, of course, a strong reflection of its creator and the talents he lends to this film. Lucas infused his upbringing and memories of cruising culture into the story and personalities. He set the tale within his hometown of Modesto and wrote three characters who personified Lucas at different points of his adolescent/young adult life. Terry serves as the nerdy high school Lucas; John is Lucas as a hot rod-driving junior college student; and Curt is the ambitious Lucas who needs to escape his hometown to fulfill his creative dreams.

Per Lucas: "It all happened to me, but I sort of glamorized it. I spent four years of my life cruising the main street of my hometown, Modesto, California. I went through all that stuff, drove the cars, bought liquor, chased girls...a very American experience. I started out as Terry the Toad, but then I went on to be John Milner, the local drag race champion, and then I became Curt Henderson, the intellectual who goes to college. They were all composite characters, based on my life, and on the lives of friends of mine. Some were killed in Vietnam, and quite a number were killed in auto accidents."

Working with a small budget on a tight 27-day schedule, Lucas had to improvise some of the filmmaking. He encouraged his cast to adlib some of their lines and movements, often choosing flubs, mistakes, and happy accidents in his final cut. He rigged a two-camera system between two adjacent moving cars to capture crosscut shots between two drivers, for example. And Lucas employed Techniscope cameras to lend the film a 16 mm appearance and more of a documentary look.

Quentin Tarantino was particularly enamored of Lucas’ directorial choices. He

said: “Lucas invokes the candy-colored pop ephemera of the fifties in his visual scheme. The green hues of the fluorescent bulbs that light the liquor stores, hamburger stands, and pinball arcades that the characters loiter around. The bright colors of the jukeboxes, diner neon signs, and the candy apple red and canary yellow of the hot rods that cruise up and down the main drag. Lucas poignantly parades all this in front of us with the added knowledge that all this glorious chrome and paint and pomade is about to go out of style and be replaced by space-age sixties chic.”

Interestingly, Lucas threw in meta nods to creations by him and producer Francis Ford Coppola, including John’s license plate (a reference to THX 1138) and Dementia 13 (Coppola’s first film), listed on the movie theater marquee.

Among several prominent themes plumbed from American Graffiti, the end of innocence permeates many scenes. This period is carefully chosen, signifying the conclusion of a simpler, safer, and more innocent age: the “golden” period of the 1950s, just before the British Invasion changed pop music forever, Kennedy was assassinated, the US entered the Vietnam War, and political and cultural turbulence took over. The postscript epilogue adds a somber tone to all we’ve seen prior: We’re told that Terry dies in Vietnam, John is killed by a drunk driver two years later, and Steve never leaves Modesto; only Curt makes it out of his hometown (living as a writer in Canada, suggesting that perhaps he chose that country to escape the draft).

Sun-Times critic Richard Roeper

wrote that 1962 was considered by many to be the “spiritual end of the 1950s…In that same vein, the film’s release in 1973 coincides with the spiritual end of the 1960s. The period piece setting and the timing of the release were just perfect…So much had transpired in our world that the relatively short, 11-year span between the time when the story is set and the release of the film seems vast.”

Ambition versus acquiescence, or growth versus stagnation, is another evident subtext. Curt is the only major player who departs his hometown. Tellingly, he’s also the sole character who finds and receives wisdom from Wolfman Jack, a Wizard of Oz-like sage who tells Curt “It’s a great big beautiful world out there.” His friend John, on the other hand, serves as the cautionary tale dramatis personae: the young man living on past glories, four years post-graduation, who knows he’s fallible and not having much luck in the ladies department.

Tarantino said of Curt’s soul searching: “Curt’s not really questioning going to college. He’s questioning the idea of leaving all the people he’s ever known. But even more than the humans he leaves behind, Curt’s questioning leaving the rituals of community that the young people of Modesto partake in… He’s the only one who realizes how temporary these rituals are. Curt knows if he gets on that airplane tomorrow morning – everything that the film so nostalgically celebrates – he can kiss all that goodbye. The town and the life he leaves, won’t be the town and the life he returns to. If he even does return, which in all likelihood, he won’t. Curt seems to know once he leaves he’s not coming back. Curt knows the boy who exists today will no longer exist even two years from now. That’s why he’s contemplating staying too long at the party…Personally, I think Curt always knew he was going to get on that airplane. He just wanted it to be his idea and not some pre-ordained destiny. His wandering around all over town all night was just Curt’s way of saying goodbye.”

Ponder, as well, how American Graffiti promulgates the “strange bedfellows,” or “opposites attract” message. Each of the main characters, or their partners, is pushed out of their comfort zone and forced or coerced to pair up with someone unexpected or opposite to their nature—usually with positive results. John is obliged to escort the much younger Carol around in his Ford Deuce Coupe but in the end doesn’t detest her company; Curt is trapped to spend the evening with a street gang but is ultimately accepted into their ranks; Candy agrees to cruise with Terry and, despite his embarrassing exploits, indicates a willingness to date him again; Laurie breaks up with Steve and drives away with bad boy Falfa, and Steve is tempted by a carhop friend, but the pair eventually reconcile.

Lucas’ work is also a rumination on the pervasive influence of pop culture and contemporary technology on our generation. American Graffiti’s adolescents live their lives around cars and cruising, radio and rock and roll, and fast food. The movie reminds us of how the suburbs burgeoned in postwar America with the building of mass highways and the proliferation of automobiles, and how dominant pop culture became geared around teenagers and their interests. Roger Ebert testified to the importance of the film as a sociocultural artifact, saying “American Graffiti is not only a great movie but a brilliant work of historical fiction; no sociological treatise could duplicate the movie’s success in remembering exactly how it was to be alive at that cultural instant.”

Lastly, consider how the film dabbles with that Melvillian trope of the elusive search for the “white whale”—or in this case, a T-Bird-driving blonde whom Curt pursues over most of the runtime, fueling his carpe diem passion and serving as a motivating muse but always remaining out of reach.

How can American Graffiti possibly feel resonant in 2023 and beyond? Many viewers can’t help but feel nostalgic for what had to be a less complicated and stressful age: a time when the joys of riding around in cars, tuning into the radio, hanging with friends minus any gadgets or social media, and hoofing it at the school dance were popular pastimes for young people. Hearing the vintage music, in particular—all-time classics by Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Bill Haley and the Comets, and The Beach Boys—makes one ponder how vital and powerful those songs must have been in their original era. American Graffiti’s greatest gift continues to be its power to transport us to a simpler time when 21st-century stressors didn’t exist. Of course, every period and generation has its advantages and disadvantages; if you were from an ethnic minority or female in 1962, it probably wasn’t such a golden age, and teenagers 60 years ago certainly faced their own unique sets of challenges. Yet as subjective and myopic as this retro vision of a departed culture may be, American Graffiti allows us to live vicariously through some captivating characters who engage in downright fun escapades and experience epiphanies large and small while also revisiting the emotional urgency, delicious self-indulgence, and motivating angst of our long-passed adolescence. As far as time capsules go, when swallowed correctly this one remains fairly potent.

Read more...