Kringle all the way

Friday, December 30, 2022

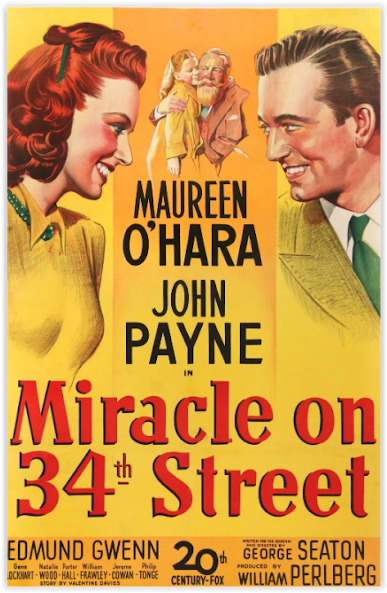

Like Santa Claus himself, Miracle on 34th Street seems to defy age as a Christmastime classic. Since 1947, it has been delighting audiences of all ages and winning over new generations of viewers, many of whom consider it every bit the equal to It’s a Wonderful Life as the ultimate yuletide flick.

Directed by George Seaton for 20th Century Fox, Miracle was a box-office winner thanks to a heartwarming script, seasonally sweet music scored by Cyril J. Mockridge, and an impeccable cast that includes Edmund Gwenn as the quintessential yet-to-be-topped Kris Kringle, Maureen O’Hara as Doris Walker, a very young Natalie Wood as her idealistic daughter Susan Walker, and John Payne as lawyer Fred Gailey.

Originally titled “The Big Heart,” Miracle on 34th Street, written by Valentine Davies, tells the story of a Macy’s store Santa Claus who converts the customers into believers of St. Nick and the altruistic Christmas spirit. Convincing the skeptical Doris and her daughter Susan, however, isn’t so easy, especially when he is put on trial to settle once and for all whether or not he is the real Kris Kringle.

The CineVerse faithful celebrated the 75th anniversary of Miracle on 34th Street last week and arrived at the following conclusions (to hear a recording of our group discussion, click here).

Directed by George Seaton for 20th Century Fox, Miracle was a box-office winner thanks to a heartwarming script, seasonally sweet music scored by Cyril J. Mockridge, and an impeccable cast that includes Edmund Gwenn as the quintessential yet-to-be-topped Kris Kringle, Maureen O’Hara as Doris Walker, a very young Natalie Wood as her idealistic daughter Susan Walker, and John Payne as lawyer Fred Gailey.

Originally titled “The Big Heart,” Miracle on 34th Street, written by Valentine Davies, tells the story of a Macy’s store Santa Claus who converts the customers into believers of St. Nick and the altruistic Christmas spirit. Convincing the skeptical Doris and her daughter Susan, however, isn’t so easy, especially when he is put on trial to settle once and for all whether or not he is the real Kris Kringle.

The CineVerse faithful celebrated the 75th anniversary of Miracle on 34th Street last week and arrived at the following conclusions (to hear a recording of our group discussion, click here).

Why is this movie worth celebrating 75 years later? Why does it still matter, and how has it stood the test of time?

- It’s sentimental at heart, but also not afraid to be worldly and cynical. It exposes the commercialization of Christmas, as well as the ties between law and politics and the dangers of pop psychology (trying to psychoanalyze someone without being qualified).

- For a film that revels in nostalgia and sentimentalism, it’s surprisingly modern in its fast pace, hustle and bustle, values and attitudes; it also helps that the Macy’s Day Parade scenes were shot on location during the actual parade in late 1946, lending a more authentic, credible feel.

- It never fully answers the central question of whether or not this film’s Kris Kringle is the real Santa Claus. Yes, he wins his court case and the hearts of Susan and her family, but the movie leaves open enough doors to suggest that this can all be rationally explained and that this is just a kindly old man who simply believes he’s Santa Claus. Or, it can suggest that this is the real Kris Kringle who has magical powers, such as the ability to bring Susan to the dream home she wanted. It balances that fine line between fantasy and reality; you can interpret it either way.

What elements from this movie have aged well, and what elements are showing some wrinkles?

- Miracle feels relatively modern and resonant in several ways.

- It presents a more secular approach to the holiday without pushing a religious message.

- It features a divorced woman and single mother who has a corporate position of power and authority.

- Susan is that rare child of divorce shown in a 1940s film.

- The movie examines the plausibility of a parent trying to prevent her child from growing up without superstitious beliefs.

- There’s a prevailing cynicism at work, too, as evidenced by the entire subplot of putting Santa Claus on trial, the judge worrying about political fallout and reelection, the media circus created around Santa and the legal hearing, and the bitter rivalry and competition between two corporate giants (Macy’s and Gimbels).

- Other aspects, however, are creaky and cringy, including Santa using violence (striking a fellow employee with a cane), Doris having a black maid, trusting in a single man you don’t know very well to babysit your child, and idealization of the nuclear family.

Major themes

- The value of faith. The movie’s central message is that faith is believing when common sense tells you not to, and “If things don’t turn out just the way you want the first time, you still have to believe.”

- What matters more: proof of a flesh and blood Santa Claus or proof of what he stands for?

- Miracle explores the dangers of growing up, prioritizing rationality and practicality at the expense of faith and belief, and the repercussions of losing the magic that motivated us as children.

- This film begs the question: Do we have the duty as parents and adults to shield children from life’s intangibles and assumedly silly beliefs?

- The commercialization of Christmas and how the values, traditions, and icons of Christmas can be turned into commodities.

- The merits of the nuclear family. This film suggests that Susan can be fully happy and fulfilled if she is nurtured by a mother and father within a loving home where she can truly enjoy her childhood. This can only be accomplished if Doris marries Fred.

How do you interpret the end of the movie, including Fred’s final line: “Maybe I didn’t do such a wonderful thing after all”?

- The presence of the cane implies that Kringle is the real Santa Claus who made Susan’s wish come true of ultimately living in a dream home. If Kringle wasn’t Santa, how did the cane get there? Kringle was locked up in Bellevue for presumably many days and wouldn’t have been able to scout and visit the home. But a supernaturally powered Santa would have.

- Or, Kringle isn’t Santa; instead, he’s merely a delusional but kindly old man. It’s possible this is all coincidental and can be rationally explained. It’s plausible that Kringle didn’t intend to secretly direct Fred and Doris to the house when he gave them directions to drive home; maybe Susan just happened to spot a house for sale that matched her dream home visions, which causes her to run into the domicile, where the grownups spot a wayward cane that appears identical to Kringle’s but is owned by someone else.

- Consider, too, that if Kringle is Santa, why doesn’t he use his supernatural powers to get himself out of Bellevue? Why does he list a New York home for the aged as his address? And how does Dr. Pierce happen to have Kris as a patient he’s very familiar with?

- Fred’s statement could be an admission that he has underestimated Kris Kringle, the non-magical person he defended at the hearing—a man who may be mentally ill yet harmless, and a person who possesses more agency and determination to prove he’s Santa than Fred had believed, as evidenced by the fact that Kringle went the extra mile to find this house and orchestrate all this matchmaking.

- Or, Fred may be stating that he isn’t such a talented attorney after all if Kris truly is the real Santa Claus with magical powers; this reading is perhaps an admission by Fred that he didn’t previously believe Kringle was the real Santa but he now does after seeing the cane, which leads him to express amazement. In this interpretation, it’s also feasible that Kringle, being a magical Santa, would have found a way to free himself from confinement regardless of Fred’s diligence.

- Ultimately, the movie works for believers and non-believers. If you want to put stock in Kringle being the genuine article, the ending offers a rewarding payoff. But even if you’re skeptical and don’t believe in Santa – either his existence in this movie or in real life – the conclusion is fulfilling because it suggests that, even if he isn’t the genuine article, what Santa stands for is real: goodwill, benevolence, love, and happiness. Because Doris and Susan are more willing to let the spirit of Santa fill their hearts and maintain a childlike sense of wonder about the world, Fred and Doris are better matched and more inclined to get married and make Susan’s dream home a reality.