Forget the sequels and reboots: The original Halloween still slashes its way to the top

Friday, October 28, 2022

None of the movies that comprise David Gordon Green's recent trilogy and reimagining of the Halloween franchise, which concludes with Halloween Ends released this month, can hold a jack-o'-lantern candle to the 1978 original helmed by John Carpenter. The 44-year-old thriller remains the benchmark against which modern horror and slasher pictures are measured, warts and all. Why does Carpenter's Halloween continue to resonate and inspire? Ponder the following points below, and click here to listen to the Cineversary podcast episode that extrapolates on what makes the film exceptional.

Why is Halloween worth celebrating all these years later? Why does it still matter, and how has it stood the test of time?

- It’s managed to stay relevant and interesting because of the quality filmmaking involved. Think about the film’s style and esthetics, the slow but regularly moving camera employed; this creates an insecure, unsettled, paranoid, distorted reality. It also makes you feel that something is lurking behind every corner, and it forces you to look for clues everywhere in the frame.

- Carpenter and cinematographer Dean Cundey craft masterful compositions: Consider the rich foregrounds, middle grounds and backgrounds, deep blacks off in the background or periphery that reveal nothing, and the wide angle lens aspect ratio. All these factors make you feel like something is hiding in the shadows, off to the side, or just out of frame.

- The focus is more on suspense than gore. Surprisingly, there is very little blood or mutilation; there is onscreen violence, but not much in terms of splatter and body parts.

- The design of this film and its elements are minimalistic but incredibly effective.

- The plot is hardly convoluted.

- The look of Michael Myers, also referred to as the shape, is hauntingly stark and plain yet terrifying, with his bleached white expressionless mask and uniformly bland mechanic’s jumpsuit.

- The music by John Carpenter, featuring only keyboards and synth sounds, uses uncomplicated but repetitive themes to ratchet up the tension.

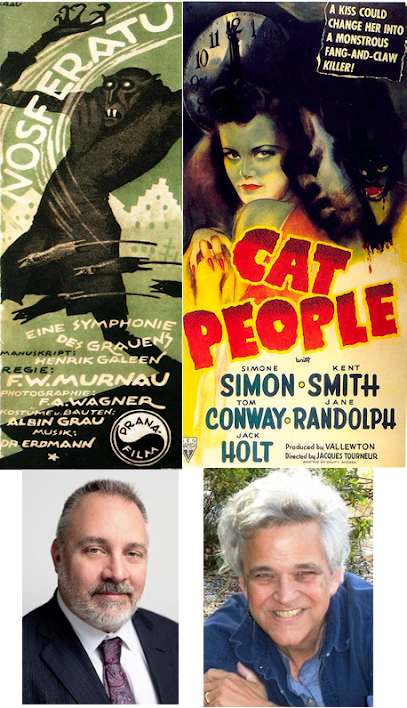

- It has also stood the test of time because Carpenter and his team learned valuable lessons from earlier horror film standouts, such as Psycho, which used a subjective camera and voyeuristic techniques that tried to make the audience intellectually/psychologically complicit in the crime. Ruminate on how the shower scene in Psycho is imitated by the young Michael Myers’ stabbing of his sister in the opening sequence.

In what ways was the film influential on cinema and popular culture or set trends?

- The subjective point of view camera shots were inspirational. We see the stalking and killings through the eyes of the killer or his victims and hear his heavy breathing. You notice this approach instantly aped in subsequent movies like the first Friday the 13th.

- This forces you into a deeper more involved participation; thus, the picture becomes a more visceral experience.

- Think about how the filmmakers often begin with wide shots and slowly move in closer, framing tighter, creating a kind of claustrophobic feeling so that the viewer can identify with a character experiencing the encroaching fear.

- The long opening take, featuring an extended tracking shot, was made possible via a Steadicam, which was a new technology at that time.

- Halloween also reinforced the convention of the final girl, earlier propagated by horror landmarks like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Black Christmas and later echoed in movies like Alien and A Nightmare on Elm Street.

- This movie suggests an eerie ambiguity about the villain, too—that Michael Myers may simply be a cunning insane person or supernaturally gifted.

- The sparse and simplistic but unnerving score by Carpenter created arguably the most instantly identifiable theme song for a horror movie and a minimalistic but effective assault on our nerves.

- Nat Brehmer of Diabolique Magazine wrote: “Halloween, with maybe the exception of Suspiria before it, was the first score to be melodic and sinister at the same time. The score is always there, drifting between two or three repeating themes, then going to a single note during acts of murder. The music is used less when Michael Myers is actually killing someone. The music aids this by focusing mostly on the tension and the buildup to the moment. Once the moment comes, the tension is over and the music drifts out.”

- When you picture Michael Myers, it’s almost impossible not to also have the theme song concurrently play in your head. That’s how powerful that score is.

- Perhaps most important of all, Halloween created an iconic, archetypal monster who has possibly become the most famous, popular, and instantly recognizable horror icon of the past 50 years. Leatherface came first, but Michael Myers set the mold for how to build a horror franchise around a killer character, a template that would be copied by the Friday the 13th, Nightmare on Elm Street, Child’s Play, and Scream films.

- Halloween launched a slew of copycat movies like When a Stranger Calls, Prom Night, Graduation Day, New Year’s Evil, Mother’s Day, My Bloody Valentine, Silent Night Deadly Night, and April Fool’s Day.

- Critics often blame Halloween for setting the slasher subgenre in motion and introducing a steady output of increasingly sadistic, gory, and misogynistic horror movies.

What themes or messages are explored in Halloween?

- Immorality will be punished: the trope of the final girl is more firmly established in this film, which suggests that Laurie Strode survives the shape’s onslaught because she is not preoccupied with sex, doesn’t indulge in promiscuity and lose her virginity, didn’t abandon the children she’s responsible for babysitting, and is smarter and demonstrates more agency than her peers.

- Arguably, this film espouses a conservative morality. Consider the evidence:

- Those who are killed are sexually promiscuous and drug users (although Laurie does take a brief puff of pot).

- According to AMC Filmsite writer Tim Dirks, Halloween “asserted the allegorical idea that sexual awakening often meant the literal 'death' of innocence (or oneself).”

- Dr. Loomis calls the boy “pure evil”; a psychiatrist is supposed to analyze human behavior, not form black-and-white moral judgements

- The film also suggests that a small, quiet town can harbor evil secrets—that there’s a dark side to suburbia.

- Halloween propagates the concept of unavoidable destiny. Laurie’s teacher says “fate is immovable, like a mountain.”

Who did the movie appeal to initially in 1978 versus today?

- Certainly Halloween attracted plenty of older teens and young adults during its initial run. Today, there’s a lot of nostalgia for the Carpenter film, which means 50-somethings and older probably place it high on their all-time horror film lists and revisit it somewhat regularly. But the fact that they’ve attempted to reboot and reinvent this franchise multiple times tells you that the original movie’s appeal spans multiple generations.

- Arguably, critics and cineastes take the 1978 movie much more seriously nowadays than back in the late 1970s, which means that it’s more deserving of critical respect and scholarly study.

What elements from this movie have aged well, and what elements are showing some wrinkles?

- The Haddonfield neighborhood doesn’t exactly “look the part.” Virtually no kids are out trick-or-treating. And there’s a dearth of autumn leaves colorfully splashed across the trees or streets.

- It’s easy to get “totally” irritated by actress P.J. Soles repeating the word “totally” throughout the picture.

- Debatably, the shot of the young Michael Myers being de-masked by his parents lingers far too long. Is it realistic to assume that mom and dad would stand nonplussed and immobile while their catatonic-looking offspring sports a bloody knife for 29 seconds?

- But these are small quibbles. Almost everything else, besides the 1970s hairstyles and wardrobe fashions, holds up very well, especially the cinematography, wide-angle compositions, editing, POV shots, creepy humor—such as when Michael Myers dons the bedsheet to fool Lynda (Soles)—and the decision to keep Michael’s face, backstory, and motivations relatively mysterious.

What is this film’s greatest gift to viewers?

- This is a high-quality horror film fans can be proud of. Considering that horror is regarded by many film critics, scholars, historians, and viewers to be a bastard stepchild genre that so often produces things putrid over pristine, it’s nice to have an unimpeachable classic that can rank high with giants of the genre like Psycho, Jaws, The Exorcist, and others.

- Plus, Michael Myers and John Carpenter’s score have become emblematic touchstones of the genre. Today, no child dresses up as Frankenstein, Dracula, or the Wolf Man on October 31 anymore; but you see plenty of kids proud to don the Michael Myers cosplay.

- Just as many people revisit old-time Christmas classics in December, like Miracle on 34th Street, It’s a Wonderful Life, and A Christmas Story, future generations will continue to watch Halloween in October. As movies and audiences continue to tolerate more violence in film as the years pass, the first Halloween film will actually be considered fairly tame as an R-rated feature, which could actually increase its reach to younger ages (hopefully with parental oversight/permission).