A South Korean masterwork that ignites our imagination

Tuesday, January 31, 2023

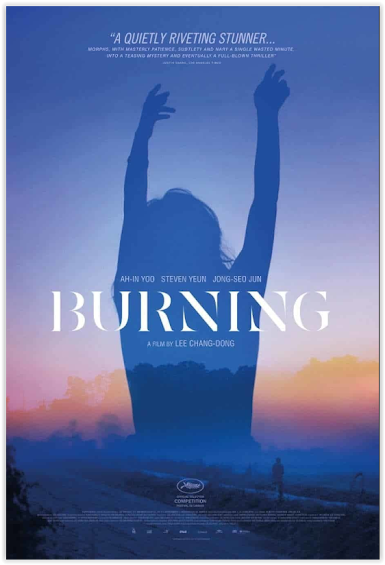

Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite took the world by storm in 2019, further demonstrating the ascendance of South Korean filmmakers and their mastery of the cinematic arts. But a key predecessor to Parasite – a movie that shares many similarities and, one could argue, is equally praiseworthy – is Burning (2018), produced, co-written, and directed by Lee Chang-dong. Last week, we at CineVerse gathered close to the brilliant light and heat generated by this film and conversed extensively about its ample virtues. Our major discussion points are outlined below (warning: spoilers ahead; click here to listen to a recording of our group discussion).

This is a picture that works on multiple levels, including multiple interpretations. Can you identify two common readings of Burning?

- A literal, more straightforward analysis is that Ben is a serial killer who enjoys murdering women of inferior status, including Hae-mi. Jong-su suspects Ben of this and ultimately kills him in an act of self-imposed justice and revenge.

- Evidence of this includes the various jewelry, presumably collected from different female victims, found in Ben’s bathroom cabinet; the sudden appearance in Ben’s building of Hae-mi’s cat, who immediately answers to the name “Boil”; Ben’s sociopathic traits, including lack of empathy and confessing to never shedding a tear; and Hae-mi’s apartment suddenly appears tidy and clean after she disappears, in contrast to the disheveled state it was in earlier.

- A different reading suggests that most or all of what we see is factual and literal up through perhaps the scene in the middle of the film where the three main characters smoke marijuana. But starting roughly from the point when Ben begins talking about burning greenhouses, the remainder of the tale is metaphoric and imaginary – within the head of aspiring novelist Jong-su, who finally has a good plot for that work of fiction he’s dreamed of writing. Keeping with the burning imagery and motifs, his imagination has been “fired up” by his exposure to Hae-mi and Ben, the former a teller of captivating but possibly untrue stories, the latter a Gatsby-like figure of fascination, and he now has more of those invaluable life experiences to fuel his writing.

- Evidence of this includes the later scene where we witness Jong-su typing on a laptop in Hae-mi’s vacated apartment; there’s also the sudden and horrific violence Jong-su unleashes upon Ben, followed by the strange behavior of removing his clothes; we also hear a character mention the word “metaphor” and explain what a metaphor is earlier in the film. In this reading of Burning, it’s likely that Ben is an elitist jerk but not a bad guy and that Hae-mi wasn’t killed but instead decided to abandon her old life and start fresh somewhere else.

Motifs and patterns

- Fire and burning. The burning in this movie takes at least three forms: the burning of kindling or combustible materials; a burning that drives your desire, whether it be sexual, spiritual, or otherwise; and an emotionally volatile burning as represented by anger and jealousy.

- Hunger, eating, and consumption – consumption of food both real and imaginary, and consumption of combustible materials like cigarettes and marijuana as well as kindling like greenhouses and human bodies.

- Running. We see both men running in different scenes and hear Hae-mi presumably running and panting on the phone.

- Dreaming. Jong-su has actual dreams he awakes from as well as aspirations and desires for something better, whether that be Hae-min as a girlfriend or the money and popularity Ben has.

- Dancing.

Major themes

- Hunger and desire. Each of the main characters craves something, whether it’s a climb up the social ladder, justice/revenge, or a higher purpose or meaning.

- Reality versus illusion or metaphor. This film juxtaposes facts and tangible/believable details with representations, speculations, possible fantasies, lies, and beliefs.

- Hai-me demonstrates how you can effectively imagine something, such as eating an invisible tangerine. She says “Don’t think there is a tangerine here. Just forget that there isn’t one. That’s the key. The important thing is to think that you really want one. Then, your mouth will water and it’ll taste really good.”

- It’s also possible Hai-me is lying about things, like owning a cat.

- Deep Focus Review blogger Brian Eggert wrote: “Burning revels in the ambiguity between the known and perceived, inhabiting the vast space between the objective and subjective. His thorny character study, its currents of class and masculine identity shaping many of its scenes over the two-and-a-half-hour runtime, portrays its themes in a way that raises more questions than it answers. And despite the viewer’s uncertainty about the motivations behind every character, or whether what unfolds in the film is what actually occurred or just our perception of it, the filmmaking somehow leaves us more engaged than if everything had been delivered gift-wrapped with a tidy bow. Lee’s interest in ambiguity further sculpts his use of the central mystery, how the characters have been written and performed, and where he chose to shoot the film.”

- Class inequality. Jong-su represents the lower class who must struggle in Korean society and who yearns for opportunity and money. Ben symbolizes the upper class and privileged in society who seemingly don’t have to work for the wealth and privilege they enjoy. Hae-mi stands between them as someone from the lower class who aims to ascend the social ladder and fit in with the upper crust. A subtheme of a classic love triangle also fits within this concept.

- Many believe this is a sociopolitical film whose key subtext preaches that these class divisions are a tinderbox waiting to ignite. With this reading, the message of class division is tied with the hunger and metaphor themes. Burning is perhaps saying that, like the imaginary tangerine, hunger by the lower classes for a better life can’t be satisfied by pretending, fancy words, illusory concepts, or trickery. If the underprivileged aren’t given real, tangible solutions, the cycle of resentment, jealousy, isolation, and ultimately violence against the empowered and upper class will continue.

- Slant Magazine critic Niles Schwartz wrote: “Jong-su, working through his literary mind, scornfully sees (Ben) as one of South Korea’s many Gatsbys, for whom work and play are indistinct, living the good life on the backs of people like Hae-mi, who will be handily disposed in time. Lee is drawing an analogy between how both authors and sociopolitical systems cast real people as abstractions or metaphors. The author or artist heightens life with metaphor, while the exploitative materialist cheapens it, and for Ben, the employment of “metaphor” implies something destructive and not creative.”

- Life is uncertain, mysterious, and unfair. There are few certainties in this story and many mysteries. From Jong-su’s perspective, his lot in life is unfair; from Ben’s point of view, assuming he is innocent of killing people, it’s undeserved that he is brutally murdered by Jong-su.

- The inability to escape your fate. Ben talks about lives as predestined by DNA or nature. Proof of this theme is played out by Jong-su, who eventually demonstrates violence as his father did.

Similar works

- Parasite

- Vertigo

- Taxi Driver

- Gone Girl

- Mulholland Drive

- The Vanishing

- Eyes Wide Shut

- Memories of Murder

- The Mad Monkey

- Classic works of American literature, including The Great Gatsby and stories by William Faulkner, including his story Barn Burning

Other films by Lee Chang-dong

- Poetry

- Secret Sunshine

- Oasis

- Peppermint Candy

- Green Fish