Fellini takes the road less traveled

Tuesday, June 13, 2023

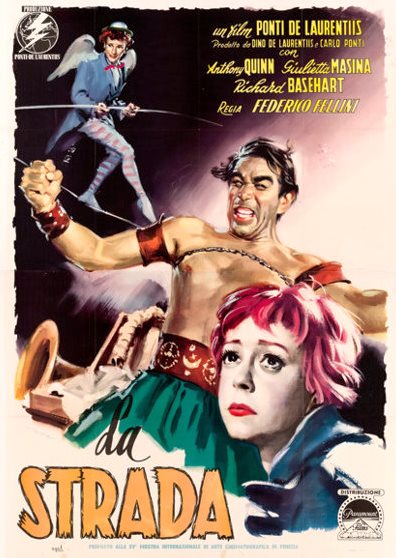

Even 69 years following its original release, Federico Fellini's La Strada remains an iconic masterwork of world cinema. The film takes us on an unforgettable journey into the life of Gelsomina, a wide-eyed young woman who is sold by her mother to Zampanò, a merciless and wandering strongman performer. Together, they traverse the picturesque landscapes of Italy, with Gelsomina enduring his mistreatment and exploitation. Their performances serve as a backdrop to their tumultuous relationship, characterized by a power dynamic of dominance and submission. Along their path, they encounter a diverse cast of characters and situations that challenge their identities and the fragile bond they share.

Fellini's artistic brilliance shines through every frame of La Strada, particularly in his unique storytelling style, which weaves together elements of poetry and dreams. The film transports us to a world that skillfully captures the profound emotions and inner conflicts of the characters, offering a profound exploration of human nature. Beyond its surface narrative, the movie’s subtextual exploration delves into universal themes of love, sacrifice, and the complexities of the human condition.

But in La Strada, professional American actors are cast. The story can be interpreted to function more as a lyrical fable, myth, or Christian allegory than a recreation of a realistic event. Magical realism is imbued in the narrative (as evidenced by Gelsomina’s wide-eyed discovery of and encounters with awe-inspiring characters like the Fool and the disabled child).

Criterion Collection essayist David Ehrenstein wrote: “Fellini’s treatment of their adventures and interactions doesn’t aim for a sense of commonality on the level usually associated with naturalism. There’s an odd touch of fantasy hanging about this childlike waif and the sullen brute who keeps her, and more than a touch of the magical to the circus high-wire walker known as The Fool, whom they meet along the way.”

In responding to his critics who accused him of betraying neorealist ideals, Fellini said: “There are more Zampanos in the world than bicycle thieves, and the story of a man who discovers his neighbor is just as important as the story of a strike.”

This film was highly influential, inspiring many filmmakers, including Akira Kurosawa, Martin Scorsese, and Krzyszlof Kieslowski, and songwriters (the tunes Me and Bobby McGee and Mr. Tambourine Man were inspired by La Strada). Its success catapulted Fellini into the pantheon of prominent figures in the film industry, paving the way for his subsequent masterpieces.

Fellini’s wife, Giulietta Masina, who plays Gelsomina, embodies this character as an instantly sympathetic child-like innocent who may be mentally challenged in addition to being naïve and inexperienced about the world. Her large, expressive eyes, squat stature, comedic timing, vulnerable demeanor, and underdog charm draw comparisons to Chaplin.

Some believe that Gelsomina represents a dated and problematic character today, as she is often bullied and tolerant of Zampano’s toxic masculinity, serving as more of a passive martyr than an inspirational character. But consider the effect her absence and death has on Zampano and the legacy she has left behind (the tune she played on trumpet that continues to be hummed and remembered by those she encountered). Recall, too, that Gelsomina, demure and passive throughout most of the story, begins to demonstrate some agency and resistance to Zampano, but ultimately proves too fragile to overcome his brutal and callous nature.

Christina Newland, another Criterion Collection essayist, wrote: “Gelsomina, a creature of luminous simplicity, suffers as though she was born to do so. And in the spiritual sense, that may be true; her suffering is purifying. There is no delusional rationalizing of an abused woman, no justification; she knows Zampanò cannot love her, that even his tiny slippages of kindness must inevitably be followed by another act of savagery. She loves him not despite his being a monster but because he is one. She may be victimized, but she is not pathetic; her self-awareness is what makes the distinction…Wretched though Gelsomina may be, she is elevated by her compassion, not her martyrdom. Even left traumatized and freezing on a roadside, she remains steadfast. In the literal sense, this seems outrageous, debased, superhuman. In the Fellinian sense, it is the most human of all gestures.”

Fascinatingly, the narrative abandons Gelsomina toward the conclusion, revealing that she had died, impoverished and sick, years earlier. We are forced to follow Zampano, the insensitive beast responsible for her demise. We see how he has further devolved since parting with his indentured servant—losing any semblance of pride in his work, drinking too much, inciting violence, and finally crawling along the shoreline with guttural cries of assumed remorse for not appreciating or reciprocating love to Gelsomina. The last shot suggests that perhaps his soul is worthy of redemption now that he has finally acknowledged his failure and his many sins; or it could be that Zampano is doomed to suffer the remainder of his life in a state of pain, grief, and regret as punishment for his transgressions.

Note that Fellini remarked that he could identify with Zampano; and he purposely cast his wife in the role of Gelsomina, which she played as a 10-year-old form of herself. A longtime philanderer, the director may have created La Strada to convey his culpability and self-admonishment.

Symbolically, Gelsomina is associated with the ocean and water, while gruff and dirty Zampano is more akin to the earth and the Fool is a light and airy creature linked to the air. In an alternate reading, she embodies the soul, Zampano the body, and the Fool the mind, per late film Pauline Kael.

The power of love and sacrifice is a resonant message espoused by La Strada. Gelsomina comes to love Zampano and feel a connection with him, a man truly unworthy of her affection. By following the Fool’s advice – that her purpose is to love Zampano – and by returning to Zampano as a loyal companion when she doesn’t have to, she willingly chooses the more difficult path, or the road less traveled, so to speak, to feel like her life has meaning.

Another key reading: Living up to your potential or fulfilling your destiny. The Fool tells Gelsomina that “everything in this world has a purpose,” even a relatively insignificant pebble, and certainly Gelsomina. He suggests that Zampano likes her but doesn’t know how to express it. The fool’s words inspire her to remain with Zampano and to encourage him to accept and, ideally, love her. She is motivated to live and work harder in her role as assistant and companion, which will hopefully make Zampano a better person who values her role in his life. Unfortunately, this choice proves to be her undoing, as Zampano fails to improve as a human being and she becomes a psychologically broken individual after he kills the Fool.

Further themes to mine include repentance and redemption. La Strada can be ultimately interpreted as an allegory about a man who recognizes and accepts – although it is too late to do anything about it – that he was loved and was capable of loving. While the story ends with this painful acknowledgment, and we don’t know what will happen to Zampano in the future, it’s possible that he learns from these experiences and becomes a better human being.

Additionally, this film serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of toxic masculinity. La Strada continues to resonate as a cautionary tale about how an imbalance between the sexes and patriarchal dominance can ultimately devastate both genders. “La Strada is best seen as a poetic expression of the yin-yang relationship between the masculine and feminine, and the destructive tendencies lurking beneath the surface of traditional masculinity. If the binary nature of Fellini’s gender politics is perhaps a bit outdated, the film’s clarity of vision is such that it remains striking both for its immediacy and the articulation of the emotions that propel its archetypal characters,” wrote Slant Magazine critic Derek Smith.

Fellini's artistic brilliance shines through every frame of La Strada, particularly in his unique storytelling style, which weaves together elements of poetry and dreams. The film transports us to a world that skillfully captures the profound emotions and inner conflicts of the characters, offering a profound exploration of human nature. Beyond its surface narrative, the movie’s subtextual exploration delves into universal themes of love, sacrifice, and the complexities of the human condition.

In 1957, La Strada was honored with the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, solidifying its esteemed place in film history. Even today, the film continues to be revered as a timeless classic, serving as a testament to Fellini's unmatched artistic vision and storytelling prowess.

This film marked a major fork in the road in Italian cinema, representing a deviation from the neorealism movement that took root over the previous nine years in Italy. Italian neorealism works were often shot in near documentary style, on location and often using nonfactors/nonprofessionals – commonly working-class people and the impoverished. The messages of neorealism films are often bleak, realistic, and plausibly pessimistic—without any sentimentalizing, glossy coating, or tacked-on happy endings. These films don’t give us black-and-white, good vs. evil tropes: characters are commonly depicted as the victims of poverty and a corrupt, unjust, and misery-inducing political system. Also, with neorealism, there is a deliberate focus away from big-name stars, complex psychological themes and issues, and intricate plots and actions.

Click here to listen to a recording of our CineVerse group discussion of La Strada, conducted last week

This film marked a major fork in the road in Italian cinema, representing a deviation from the neorealism movement that took root over the previous nine years in Italy. Italian neorealism works were often shot in near documentary style, on location and often using nonfactors/nonprofessionals – commonly working-class people and the impoverished. The messages of neorealism films are often bleak, realistic, and plausibly pessimistic—without any sentimentalizing, glossy coating, or tacked-on happy endings. These films don’t give us black-and-white, good vs. evil tropes: characters are commonly depicted as the victims of poverty and a corrupt, unjust, and misery-inducing political system. Also, with neorealism, there is a deliberate focus away from big-name stars, complex psychological themes and issues, and intricate plots and actions.

But in La Strada, professional American actors are cast. The story can be interpreted to function more as a lyrical fable, myth, or Christian allegory than a recreation of a realistic event. Magical realism is imbued in the narrative (as evidenced by Gelsomina’s wide-eyed discovery of and encounters with awe-inspiring characters like the Fool and the disabled child).

Criterion Collection essayist David Ehrenstein wrote: “Fellini’s treatment of their adventures and interactions doesn’t aim for a sense of commonality on the level usually associated with naturalism. There’s an odd touch of fantasy hanging about this childlike waif and the sullen brute who keeps her, and more than a touch of the magical to the circus high-wire walker known as The Fool, whom they meet along the way.”

In responding to his critics who accused him of betraying neorealist ideals, Fellini said: “There are more Zampanos in the world than bicycle thieves, and the story of a man who discovers his neighbor is just as important as the story of a strike.”

This film was highly influential, inspiring many filmmakers, including Akira Kurosawa, Martin Scorsese, and Krzyszlof Kieslowski, and songwriters (the tunes Me and Bobby McGee and Mr. Tambourine Man were inspired by La Strada). Its success catapulted Fellini into the pantheon of prominent figures in the film industry, paving the way for his subsequent masterpieces.

Fellini’s wife, Giulietta Masina, who plays Gelsomina, embodies this character as an instantly sympathetic child-like innocent who may be mentally challenged in addition to being naïve and inexperienced about the world. Her large, expressive eyes, squat stature, comedic timing, vulnerable demeanor, and underdog charm draw comparisons to Chaplin.

Some believe that Gelsomina represents a dated and problematic character today, as she is often bullied and tolerant of Zampano’s toxic masculinity, serving as more of a passive martyr than an inspirational character. But consider the effect her absence and death has on Zampano and the legacy she has left behind (the tune she played on trumpet that continues to be hummed and remembered by those she encountered). Recall, too, that Gelsomina, demure and passive throughout most of the story, begins to demonstrate some agency and resistance to Zampano, but ultimately proves too fragile to overcome his brutal and callous nature.

Christina Newland, another Criterion Collection essayist, wrote: “Gelsomina, a creature of luminous simplicity, suffers as though she was born to do so. And in the spiritual sense, that may be true; her suffering is purifying. There is no delusional rationalizing of an abused woman, no justification; she knows Zampanò cannot love her, that even his tiny slippages of kindness must inevitably be followed by another act of savagery. She loves him not despite his being a monster but because he is one. She may be victimized, but she is not pathetic; her self-awareness is what makes the distinction…Wretched though Gelsomina may be, she is elevated by her compassion, not her martyrdom. Even left traumatized and freezing on a roadside, she remains steadfast. In the literal sense, this seems outrageous, debased, superhuman. In the Fellinian sense, it is the most human of all gestures.”

Fascinatingly, the narrative abandons Gelsomina toward the conclusion, revealing that she had died, impoverished and sick, years earlier. We are forced to follow Zampano, the insensitive beast responsible for her demise. We see how he has further devolved since parting with his indentured servant—losing any semblance of pride in his work, drinking too much, inciting violence, and finally crawling along the shoreline with guttural cries of assumed remorse for not appreciating or reciprocating love to Gelsomina. The last shot suggests that perhaps his soul is worthy of redemption now that he has finally acknowledged his failure and his many sins; or it could be that Zampano is doomed to suffer the remainder of his life in a state of pain, grief, and regret as punishment for his transgressions.

Note that Fellini remarked that he could identify with Zampano; and he purposely cast his wife in the role of Gelsomina, which she played as a 10-year-old form of herself. A longtime philanderer, the director may have created La Strada to convey his culpability and self-admonishment.

Symbolically, Gelsomina is associated with the ocean and water, while gruff and dirty Zampano is more akin to the earth and the Fool is a light and airy creature linked to the air. In an alternate reading, she embodies the soul, Zampano the body, and the Fool the mind, per late film Pauline Kael.

The power of love and sacrifice is a resonant message espoused by La Strada. Gelsomina comes to love Zampano and feel a connection with him, a man truly unworthy of her affection. By following the Fool’s advice – that her purpose is to love Zampano – and by returning to Zampano as a loyal companion when she doesn’t have to, she willingly chooses the more difficult path, or the road less traveled, so to speak, to feel like her life has meaning.

Another key reading: Living up to your potential or fulfilling your destiny. The Fool tells Gelsomina that “everything in this world has a purpose,” even a relatively insignificant pebble, and certainly Gelsomina. He suggests that Zampano likes her but doesn’t know how to express it. The fool’s words inspire her to remain with Zampano and to encourage him to accept and, ideally, love her. She is motivated to live and work harder in her role as assistant and companion, which will hopefully make Zampano a better person who values her role in his life. Unfortunately, this choice proves to be her undoing, as Zampano fails to improve as a human being and she becomes a psychologically broken individual after he kills the Fool.

Further themes to mine include repentance and redemption. La Strada can be ultimately interpreted as an allegory about a man who recognizes and accepts – although it is too late to do anything about it – that he was loved and was capable of loving. While the story ends with this painful acknowledgment, and we don’t know what will happen to Zampano in the future, it’s possible that he learns from these experiences and becomes a better human being.

Additionally, this film serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of toxic masculinity. La Strada continues to resonate as a cautionary tale about how an imbalance between the sexes and patriarchal dominance can ultimately devastate both genders. “La Strada is best seen as a poetic expression of the yin-yang relationship between the masculine and feminine, and the destructive tendencies lurking beneath the surface of traditional masculinity. If the binary nature of Fellini’s gender politics is perhaps a bit outdated, the film’s clarity of vision is such that it remains striking both for its immediacy and the articulation of the emotions that propel its archetypal characters,” wrote Slant Magazine critic Derek Smith.

Similar works

- Beauty and the Beast

- Raging Bull

- Sweet and Lowdown

- Films by Charlie Chaplin, including The Circus

Other prominent films by Fellini

- I Vitelloni

- Nights of Cabiria

- La Dolce Vita

- 8½

- Juliet of the Spirits

- Roma

- Amarcord