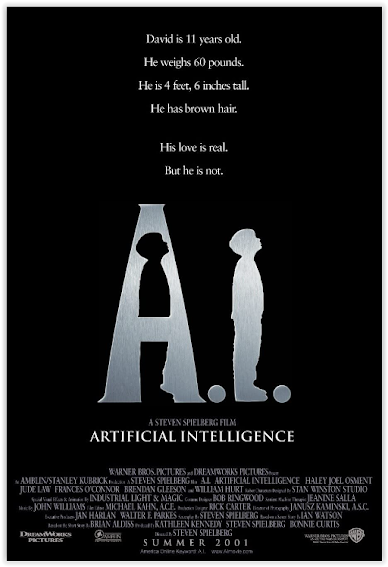

His love is real, but he is not

Wednesday, April 5, 2023

AI: Artificial Intelligence, directed by Steven Spielberg, the science-fiction drama released in 2001, depicts a futuristic world where robots have become commonplace, and a highly advanced robotic boy named David, played by Haley Joel Osment, is created to serve as a substitute for a couple's comatose son. As David navigates through a series of trials and tribulations, he sets out on a quest to become a real boy and find his place in a world that is both fascinated and fearful of artificial intelligence.

To listen to a recording of our CineVerse group discussion of this film conducted last week, click here.

The film was inspired by Brian Aldiss's short story "Supertoys Last All Summer Long.” It received mixed reviews upon release, with some praising its ambition and visual effects, while others criticized its tonal inconsistencies. However, it has since become a cult classic and is considered a landmark in the genre of science fiction.

What’s impressive about this film? It’s an amalgam project that showcases the sensibilities and stylistic choices of the two directors associated with it: Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick. Kubrick was enamored with Aldiss’ original short story and developed it into several screenplay iterations but couldn’t advance his vision for the film until special effects were up to the task of creating this world of ultra-realistic artificial beings. Eventually, he passed the project entirely onto Spielberg, who declined to make it until after Kubrick passed away in 1999.

Kubrick’s films were often known for their cool detachment, cynicism, and unsentimental narrative approaches, while Spielberg was famous for helming more humanistic movies and infusing sentimentality into his productions. But interestingly, it was Kubrick who insisted on the film’s emotionally bittersweet epilogue and many of the fairytale elements of the story, while Spielberg shows a deft hand by applying Kubrickian-like pessimism, violence, and sexuality.

The visuals in AI are often never less than stunning, with individual shots long remaining in the viewer’s consciousness, including dreamlike imagery of David and Teddy walking through the dark forest at night and spotting the impossibly rotund and glowing moon as well as the spellbinding shots of the submerged David staring wishfully at the blue fairy statue. The visual and makeup effects here are exemplary.

AI was not widely accepted or beloved on its release in the summer of 2001. It struggled to earn back its budget and wow many critics and audiences. Perhaps a reason for its box office failure and lack of mainstream acceptance is that audiences could not, at least at that time, identify with David and his ability to love unconditionally, even if it was human-programmed love. Additionally, the melding of messages about childlike innocence and storybook fantasy with decidedly adult themes of human intolerance, ugliness, and barbarism might have been a difficult bouillabaisse to swallow.

Interestingly, the film is roughly divided into four distinctive parts: David acclimating to and ultimately being rejected from his new family environment; David and friends on the run from human predators; David on a mission to find the blue fairy; and the realization of sorts of David’s dream.

Significantly, the artificial beings in this film are often more sympathetic and relatable to us than most of the human characters, many of whom are cruel, capricious, cold, and calculating. The filmmakers continually frame and shoot the narrative’s perspective from the viewpoint of David and other mechas. Time and again Spielberg gives us mirror reflections, shots of David looking through masks or eyeholes, and POV shots of artificially intelligent creations looking out upon the world (for example, the camera swings across to give us the point of view shot of the AI seer Mr. Know).

It’s also noteworthy that the harsh realities of climate change are reflected in this fictional story, which helps it age better after 22 years.

The picture benefits from being embedded with several crucial messages. Of particular thematic resonance is the exploration of an ultra-modern Prometheus. AI: Artificial Intelligence is a loose reworking of the Pinocchio story but also the Frankenstein myth, in which a brilliant scientist creates a new form of life with the blessing and curse of loving unconditionally and feeling emotional pain. Like the Frankenstein monster who was rejected and forsaken by his maker, David is discarded and abandoned by his mother.

The film also espouses that we bear a responsibility and moral liability as human beings for having created and promoted artificial intelligence, which may ultimately replace us.

Additionally, AI: Artificial Intelligence asks a vital question: What truly distinguishes a human being from an artificial being? Like the AI represented by David, we are machines of sorts, programmed by nature, instinct, and DNA, to seek love and acceptance and survive. Is it truly correct to assume that David is merely driven by human-imposed technological programming and that any emotion he thinks he is experiencing isn’t real – it’s instead a simulation of a feeling or clever puppeteering on the part of his human makers? AI: Artificial Intelligence challenges us consistently: If our ability as human beings to feel and express emotions and empathy is what separates us from lower life forms and makes us more “human,” is it then wrong to attempt to create an artificial human possessing or at least aspiring to the same qualities? If artificial intelligence outlasts and replaces us, as many predict, is it a more or less comforting thought that future artificial beings will aim to perpetuate the best aspects of humanity, including love, empathy, and tolerance (which seem to be among the traits expressed by the advanced synthetic beings who extract David from the ice and attempt to make his dream come true)?

As downbeat, bittersweet, and harsh as this film can feel through much of its run time, the conclusion is arguably an optimistic one. It suggests that, if it’s inevitable that humans will be replaced by the artificial intelligence it created, the upside is that future AI beings will represent the best of what humanity was capable of: empathy, compassion, acceptance, and kindness. Future AI will ideally adopt the best humanistic and emotional aspects of modern homo sapiens so that humanity lives on, in a way. The bridge between the 22nd century depicted in this story and advanced AI 2000 years later is David, who first proved that AI could, through human programming, love unconditionally and dream. The synthetic creatures – who are apparently not extraterrestrials but advanced versions of sentiment robots – desire to fulfill David’s wish and make him a “real boy” in a manner of speaking by using technology (another form of magic) to conjure up his dead mother and enable the boy bot to feel loved. Why would they go to the effort of finding and resuscitating David and processing all of his memories if not to fulfill his desires in a compassionate act? Otherwise, what’s in it for them?

To listen to a recording of our CineVerse group discussion of this film conducted last week, click here.

The film was inspired by Brian Aldiss's short story "Supertoys Last All Summer Long.” It received mixed reviews upon release, with some praising its ambition and visual effects, while others criticized its tonal inconsistencies. However, it has since become a cult classic and is considered a landmark in the genre of science fiction.

What’s impressive about this film? It’s an amalgam project that showcases the sensibilities and stylistic choices of the two directors associated with it: Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick. Kubrick was enamored with Aldiss’ original short story and developed it into several screenplay iterations but couldn’t advance his vision for the film until special effects were up to the task of creating this world of ultra-realistic artificial beings. Eventually, he passed the project entirely onto Spielberg, who declined to make it until after Kubrick passed away in 1999.

Kubrick’s films were often known for their cool detachment, cynicism, and unsentimental narrative approaches, while Spielberg was famous for helming more humanistic movies and infusing sentimentality into his productions. But interestingly, it was Kubrick who insisted on the film’s emotionally bittersweet epilogue and many of the fairytale elements of the story, while Spielberg shows a deft hand by applying Kubrickian-like pessimism, violence, and sexuality.

The visuals in AI are often never less than stunning, with individual shots long remaining in the viewer’s consciousness, including dreamlike imagery of David and Teddy walking through the dark forest at night and spotting the impossibly rotund and glowing moon as well as the spellbinding shots of the submerged David staring wishfully at the blue fairy statue. The visual and makeup effects here are exemplary.

AI was not widely accepted or beloved on its release in the summer of 2001. It struggled to earn back its budget and wow many critics and audiences. Perhaps a reason for its box office failure and lack of mainstream acceptance is that audiences could not, at least at that time, identify with David and his ability to love unconditionally, even if it was human-programmed love. Additionally, the melding of messages about childlike innocence and storybook fantasy with decidedly adult themes of human intolerance, ugliness, and barbarism might have been a difficult bouillabaisse to swallow.

Interestingly, the film is roughly divided into four distinctive parts: David acclimating to and ultimately being rejected from his new family environment; David and friends on the run from human predators; David on a mission to find the blue fairy; and the realization of sorts of David’s dream.

Significantly, the artificial beings in this film are often more sympathetic and relatable to us than most of the human characters, many of whom are cruel, capricious, cold, and calculating. The filmmakers continually frame and shoot the narrative’s perspective from the viewpoint of David and other mechas. Time and again Spielberg gives us mirror reflections, shots of David looking through masks or eyeholes, and POV shots of artificially intelligent creations looking out upon the world (for example, the camera swings across to give us the point of view shot of the AI seer Mr. Know).

It’s also noteworthy that the harsh realities of climate change are reflected in this fictional story, which helps it age better after 22 years.

The picture benefits from being embedded with several crucial messages. Of particular thematic resonance is the exploration of an ultra-modern Prometheus. AI: Artificial Intelligence is a loose reworking of the Pinocchio story but also the Frankenstein myth, in which a brilliant scientist creates a new form of life with the blessing and curse of loving unconditionally and feeling emotional pain. Like the Frankenstein monster who was rejected and forsaken by his maker, David is discarded and abandoned by his mother.

The film also espouses that we bear a responsibility and moral liability as human beings for having created and promoted artificial intelligence, which may ultimately replace us.

Additionally, AI: Artificial Intelligence asks a vital question: What truly distinguishes a human being from an artificial being? Like the AI represented by David, we are machines of sorts, programmed by nature, instinct, and DNA, to seek love and acceptance and survive. Is it truly correct to assume that David is merely driven by human-imposed technological programming and that any emotion he thinks he is experiencing isn’t real – it’s instead a simulation of a feeling or clever puppeteering on the part of his human makers? AI: Artificial Intelligence challenges us consistently: If our ability as human beings to feel and express emotions and empathy is what separates us from lower life forms and makes us more “human,” is it then wrong to attempt to create an artificial human possessing or at least aspiring to the same qualities? If artificial intelligence outlasts and replaces us, as many predict, is it a more or less comforting thought that future artificial beings will aim to perpetuate the best aspects of humanity, including love, empathy, and tolerance (which seem to be among the traits expressed by the advanced synthetic beings who extract David from the ice and attempt to make his dream come true)?

As downbeat, bittersweet, and harsh as this film can feel through much of its run time, the conclusion is arguably an optimistic one. It suggests that, if it’s inevitable that humans will be replaced by the artificial intelligence it created, the upside is that future AI beings will represent the best of what humanity was capable of: empathy, compassion, acceptance, and kindness. Future AI will ideally adopt the best humanistic and emotional aspects of modern homo sapiens so that humanity lives on, in a way. The bridge between the 22nd century depicted in this story and advanced AI 2000 years later is David, who first proved that AI could, through human programming, love unconditionally and dream. The synthetic creatures – who are apparently not extraterrestrials but advanced versions of sentiment robots – desire to fulfill David’s wish and make him a “real boy” in a manner of speaking by using technology (another form of magic) to conjure up his dead mother and enable the boy bot to feel loved. Why would they go to the effort of finding and resuscitating David and processing all of his memories if not to fulfill his desires in a compassionate act? Otherwise, what’s in it for them?

Similar works

- Pinocchio, Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, and other fairytale stories

- The myth of Oedipus

- Shelley’s Frankenstein

- The Wizard of Oz

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Ex Machina

- Bicentennial Man

- Robocop

- The early 1960s anime series Astro Boy