Neighbors from hell

Tuesday, April 18, 2023

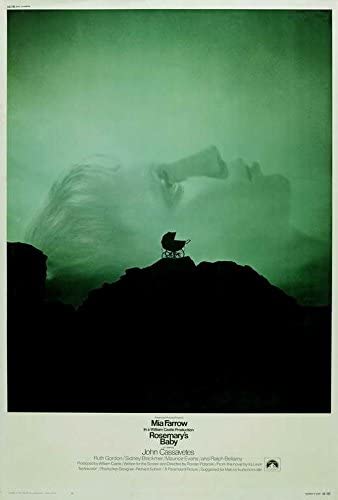

Rosemary's Baby, directed by Roman Polanski and based on the novel by Ira Levin, is an unforgettable psychological horror movie that follows the story of a young woman named Rosemary who moves into a new apartment with her husband and becomes pregnant. However, as her pregnancy progresses, she begins to suspect that something is not quite right with her unborn child and that her neighbors are involved in a dark conspiracy.

When the film was released in 1968, it was a commercial and critical triumph and is now regarded as a classic in the horror genre. The picture’s significance lies in the way it shifted the genre's focus from traditional supernatural monsters to more psychological fears, exploring themes such as paranoia, loss of control, and isolation, which resonated with the audience, especially women. Today, it's especially praised for its feminist themes and remains significant for marking a turning point in Polanski's career, as it was his first American film, which helped establish him as a prominent director in Hollywood. Rosemary's Baby also paved the way for a new wave of serious adult horror cinema, including The Exorcist, The Omen, and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in the 1970s.

To listen to a recording of our CineVerse group discussion of this movie, conducted last week, click here.

What makes this film so frightening and disturbing? Rosemary’s Baby preys upon our fears of being alienated, conspired against, exploited, outnumbered, and ignorant about the dangers around us. The victim is an innocent, decreasingly naïve, and expectant mother whose unborn child is also at risk. This narrative depicts a horrifying world where a modern perverse subculture could be congregating right next door, and in broad daylight. What’s more, the film contains several unnervingly eerie dream sequences that have spurred innumerable nightmares for moviegoers, including a satanic rape scene that’s unsettling enough in its suggestive imagery without being tastelessly graphic.

Rosemary’s Baby benefits from proper character development, a story that builds patiently and reliably, realistic dialogue, and plausible personality behaviors. Moreover, this work is artfully directed and carefully crafted. Consider the scene where a distraught Rosemary walks aimlessly into oncoming car traffic, which was shot personally by Polanski using a handheld camera to capture the spontaneity and real-life danger of this event. Also, ponder the frequent use of a mobile camera as the lens increasingly tracks along queasily with Rosemary as she begins to uncover the truth; this choice lends the film a nervous “you-are-there” verisimilitude.

Rosemary’s Baby uses sound inventively, too, as proven by often disquietingly low-volume scenes in which we, like our heroine, must listen carefully for audio clues near her environment, such as a newborn’s cry or the voices behind the wall.

Much is also accomplished via ideal casting. John Cassavetes, underrated as an actor plays Rosemary’s husband, a conniving, down-on-his-luck thespian. Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer shine as Rosemary’s creepy next-door neighbors, and Ralph Bellamy and Charles Grodin are equally convincing as her physicians.

The movie can perhaps be viewed as an outmoded artifact of its time—the late sixties, when the youth counterculture was robust and the motto was “Don’t trust anyone over 30.” But the concepts and themes explored in Rosemary’s Baby are ageless. This film is fueled by numerous ideas and messages, including isolation, mistrust, gaslighting, loss of agency, a woman’s right to her body, patriarchal subjugation, prevalent and persistent sexism in society, the presence of evil where it’s least expected—your own home—and the discomforts and anxieties that can accompany being pregnant.

Some argue that the conclusion is anti-climactic and disappointing. Others insist that the dénouement is chillingly effective. (SPOILERS AHEAD) On one hand, it’s a bit hard to swallow that Rosemary would ostensibly agree to nurture and mother her devilish offspring, considering how enraged she must be at the conspirators and the fact that she’s a Catholic. Yet it also makes sense that her maternal instincts would inevitably kick in and that she would want to protect her son from bad influences him. However, if it’s assumed that Rosemary acquiesces and enlists as the primary caregiver, it’s also doubtful that she will be able to thwart the designs of the coven or indefinitely resist the group’s persuasion to join them in their rituals and lifestyle. That reading layers an extra dark pessimism onto the ending that can be interpreted as, ultimately, evil conquers all.

For those unsatisfied by the finish, remember that it’s not as important that we got to this point: the unsettling journey along the way and the erosion of your comfort and confidence as a viewer is what truly matters.

When the film was released in 1968, it was a commercial and critical triumph and is now regarded as a classic in the horror genre. The picture’s significance lies in the way it shifted the genre's focus from traditional supernatural monsters to more psychological fears, exploring themes such as paranoia, loss of control, and isolation, which resonated with the audience, especially women. Today, it's especially praised for its feminist themes and remains significant for marking a turning point in Polanski's career, as it was his first American film, which helped establish him as a prominent director in Hollywood. Rosemary's Baby also paved the way for a new wave of serious adult horror cinema, including The Exorcist, The Omen, and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in the 1970s.

To listen to a recording of our CineVerse group discussion of this movie, conducted last week, click here.

What makes this film so frightening and disturbing? Rosemary’s Baby preys upon our fears of being alienated, conspired against, exploited, outnumbered, and ignorant about the dangers around us. The victim is an innocent, decreasingly naïve, and expectant mother whose unborn child is also at risk. This narrative depicts a horrifying world where a modern perverse subculture could be congregating right next door, and in broad daylight. What’s more, the film contains several unnervingly eerie dream sequences that have spurred innumerable nightmares for moviegoers, including a satanic rape scene that’s unsettling enough in its suggestive imagery without being tastelessly graphic.

Rosemary’s Baby benefits from proper character development, a story that builds patiently and reliably, realistic dialogue, and plausible personality behaviors. Moreover, this work is artfully directed and carefully crafted. Consider the scene where a distraught Rosemary walks aimlessly into oncoming car traffic, which was shot personally by Polanski using a handheld camera to capture the spontaneity and real-life danger of this event. Also, ponder the frequent use of a mobile camera as the lens increasingly tracks along queasily with Rosemary as she begins to uncover the truth; this choice lends the film a nervous “you-are-there” verisimilitude.

Rosemary’s Baby uses sound inventively, too, as proven by often disquietingly low-volume scenes in which we, like our heroine, must listen carefully for audio clues near her environment, such as a newborn’s cry or the voices behind the wall.

Much is also accomplished via ideal casting. John Cassavetes, underrated as an actor plays Rosemary’s husband, a conniving, down-on-his-luck thespian. Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer shine as Rosemary’s creepy next-door neighbors, and Ralph Bellamy and Charles Grodin are equally convincing as her physicians.

The movie can perhaps be viewed as an outmoded artifact of its time—the late sixties, when the youth counterculture was robust and the motto was “Don’t trust anyone over 30.” But the concepts and themes explored in Rosemary’s Baby are ageless. This film is fueled by numerous ideas and messages, including isolation, mistrust, gaslighting, loss of agency, a woman’s right to her body, patriarchal subjugation, prevalent and persistent sexism in society, the presence of evil where it’s least expected—your own home—and the discomforts and anxieties that can accompany being pregnant.

Some argue that the conclusion is anti-climactic and disappointing. Others insist that the dénouement is chillingly effective. (SPOILERS AHEAD) On one hand, it’s a bit hard to swallow that Rosemary would ostensibly agree to nurture and mother her devilish offspring, considering how enraged she must be at the conspirators and the fact that she’s a Catholic. Yet it also makes sense that her maternal instincts would inevitably kick in and that she would want to protect her son from bad influences him. However, if it’s assumed that Rosemary acquiesces and enlists as the primary caregiver, it’s also doubtful that she will be able to thwart the designs of the coven or indefinitely resist the group’s persuasion to join them in their rituals and lifestyle. That reading layers an extra dark pessimism onto the ending that can be interpreted as, ultimately, evil conquers all.

For those unsatisfied by the finish, remember that it’s not as important that we got to this point: the unsettling journey along the way and the erosion of your comfort and confidence as a viewer is what truly matters.

Similar works

- Hitchcock’s Suspicion, in which a wife begins to suspect the worst about her husband

- The Omen, in which a couple’s adopted child may or may not be the spawn of Satan, and the parent cannot bring himself to kill the child.

- Polanski’s earlier Repuslion, wherein a young woman gradually descends into a sexually-distorted paranoia and debilitating madness, and the director’s subsequent The Tenant, which tells the story of an increasingly paranoid and persecuted man renting an apartment in a building occupied by weird denizens.

- House of the Devil

- Hereditary

- Gaslight

- Lyle

- The Witch

- Suspiria