The last word on Safety Last!

Friday, April 28, 2023

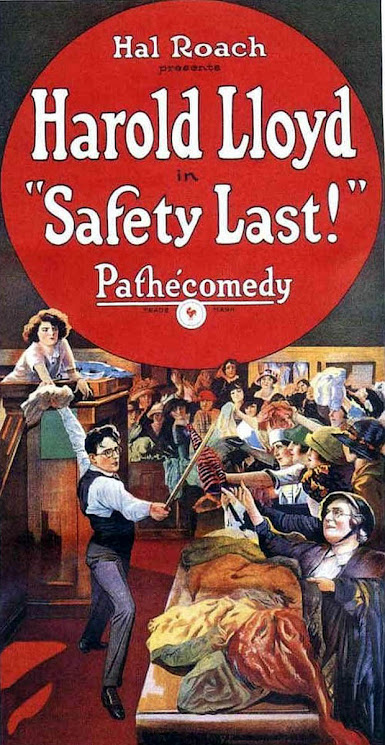

There are at least 100 reasons—and now, 100 years—why Safety Last! remains an all-time classic silent comedy. Directed by Fred C. Newmeyer and Sam Taylor, produced by Hal Roach, and starring Harold Lloyd – one of the most popular and influential comedians of the silent film era – the film tells the story of a young man named Harold who moves to the city to make his fortune and impress his girlfriend. He takes a job in a department store and comes up with a scheme to climb the building to promote a publicity stunt for the store. However, his climb becomes increasingly perilous, leading to a series of hilarious and suspenseful set-pieces.

To hear a recording of our CineVerse group discussion of this film, conducted last year, click here; to listen to our current Cineversary podcast episode on Safety Last!, click here.

Safety Last! deserves to be celebrated a century not just because it’s a timeless laugher with a higher ratio of yuks per minute than any silent film or classic movie ever made. It also features the most instantly recognizable image in silent films: a bespectacled man hanging from a clock face 12 stories above the ground. The ubiquity and – no pun intended – the timelessness of this image underscores how important and beloved this film remains in pop culture. As proof of how pervasive this iconography is, recall the CoverGirl Outlast TV commercial from 10 years ago featuring actress Sophia Vergara hanging from a giant clock face that resembles the one in Safety Last!

The events and incredible stunts appear and feel real, largely because the movie was shot on location outdoors in Los Angeles using actual buildings and featuring non-acting crowds that arrived to watch. It also looks authentic because Harold Lloyd and a human fly stuntman actually scaled that building, with a circus performer used for the foot-hanging-from-a-rope scene. Lloyd and these performers took significant risks and jeopardized their lives to make the action appear as genuine as possible. Bear in mind that the filmmakers don’t use special effects like matte paintings or rear screen projection. Lloyd’s stunt work is all the more remarkable considering that he lost a thumb and index finger on one of his hands a few years earlier.

Additionally, the picture goes non-stop without any slowdown or weak scenes and is chock full of great jokes and gags—the finest and most extended of which is the scaling of the building—but there are gags within gags and climaxes within climaxes that layer the film with comedy and thrills. Amazingly, however, this 73-minute film only has about 10 scenes. The cinematography here is advanced for a 1923 comedy. Safety Last!, especially in its last half hour, benefits from the use of varying camera angles – including POV shots – and recurrent movement of the camera.

Despite its reputation as one of the greatest and funniest silent comedies, arguably, Safety Last is more entertaining and fulfilling as an action thriller than a comedy. Some film historians and scholars credit Safety Last as the progenitor of a particular genre. “The structure of Safety Last!...is instantly recognizable to the modern viewer,” wrote Criterion Collection essayist Ed Park. “It’s still the template for the contemporary action flick, in which the story sets up a spectacular chase or fight sequence at the end.”

Interestingly, although the film is remembered for its outdoor climbing sequences and close calls, the movie’s first half primarily takes place indoors while outside scenes dominate the second half.

Lloyd, unlike Charles Chaplin and Buster Keaton, benefited from an everyman look and quality as well as his rounded spectacles, which gave him a more intelligent yet fallible appearance. Lloyd is billed as “the boy,” but his employee card clearly lists him as “Harold Lloyd.” Chaplin had The Little Tramp, and Lloyd had this character, often referred to as “Glasses.” Lloyd said in interviews: “Someone with glasses is generally thought to be studious and an erudite person to a degree, a kind of person who doesn’t fight or engage in violence, but I did, so my glasses belied my appearance. The audience could put me in a situation with that in mind, but I could be just the opposite of what was supposed…In the pictures that I did, I could be an introvert, a little weakling, and another could be an extrovert, the sophisticate, the hypochondriac. They looked alike in appearance, with the glasses, which I guess you’d call a typical American boy.”

Like Keaton, Lloyd’s characters also used improvisational resourcefulness to ingeniously get out of jambs. For instance, in Safety Last, he and his roommate hang hilariously beneath coats on hooks from the landlady, he crawls beside a box to get away from the floorwalker, and when he falls he immediately does push-ups to save face.

Chaplin infused more sentimentality, emotionality, and pathos into his characters and situations and typically portrayed a more lonely and solitary figure in The Little Tramp. Keaton leaned more heavily on getting laughs and incorporating slapstick and stunts in his pictures and often maintained a stoic, deadpan expression. Like Keaton, Lloyd often employed impressive and inventive stunt work and physical comedy and embodied everyman characters at odds with an increasingly chaotic world; in fact, several of Keaton’s films echo shots, gags, and stories from Lloyd’s works and vice versa. However, Lloyd preferred to play more optimistic, enthusiastic, likable, all-American types who commonly struggle to keep pace with a hectic contemporary world.

Speculating on how Chaplin or Keaton might have approached this film, DVD Savant Glenn Erickson posited: “Charlie Chaplin would turn tail and run, or blunder into the problem wearing a blindfold and find out only later how much danger he was in. Keaton would envision the crisis as a series of fantastic mechanical challenges, relying on the 'harmonious chaos' of physical reality to save his skin. Harold's extended building climb is a crazy gauntlet of dangers and accidents within accidents…Harold may be crazy but he never gives up. He's got the right stuff to (literally) reach the top.”

Longtime collaborator Hal Roach remarked of his friend: “Harold Lloyd worked for me because he could play a comedian. He was not a comedian. He was the best actor I ever saw being a comedian . . . No one worked harder than he did.”

Fascinatingly, Lloyd made more films and money than Chaplin and Keaton combined in their prime years. Roger Ebert wrote: “I could understand why Lloyd outgrossed Chaplin and Keaton in the 1920s: Not because he was funnier or more poignant, but because he was merely mortal and their characters were from another plane of existence. Lloyd is a real man climbing a building; Keaton, as he stands just exactly where a building will not crush him, is an instrument of cosmic fate. And Chaplin is a visitor to our universe from the one that exists in his mind… Perhaps that is what makes him special: (Lloyd) is determined to be a great silent comedian, and succeeds by experimentation, courage, and will. His films are about his triumph over their making.”

Perhaps a case can be made that certain later films by Chaplin and Keaton, including The General, Steamboat Bill, Jr., The General, and Modern Times, were partially inspired by Safety Last! Possibly the ascent of the Empire State Building in King Kong 10 years later took a cue from this movie, as did the first Die Hard film, in which John McClane must traverse the various stories of a skyscraper in superhuman fashion. Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol features Tom Cruise performing extraordinary stunts along the side of a Dubai skyscraper, and the documentary Man on Wire details a gripping tightrope walk between The Twin Towers – two movies that instantly bring Safety Last! to mind. And films that pay homage to Safety Last! include Stanley Kramer’s It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, The Jackie Chan martial arts comedy Project A, the first Back to the Future film, The Hudsucker Proxy, and Martin Scorsese’s Hugo.

While it’s not a thematically rich film, subtexts are present in Safety Last! if you want to look for them. One is good and bad timing: The boy is pressured to arrive at work on time, and frequently it appears that time is not on his side, yet an actual clock face serves as a lifeline and he continually has the benefit of fortuitous timing. Ponder, as well, all the visual nods to time: the clock face, his body swinging like a pendulum, and the work time clock. From the start, we are told in an intertitle: “The boy was always early.”

The economic and practical challenges of surviving and coping in an increasingly industrialized metropolis are other takeaways. From public transportation that can’t accommodate him to throngs of angry customers seeking service in a busy department store, the boy is faced with one obstacle after another. In his review for Slant Magazine, Calum Marsh commented: “Lloyd’s clock-stopping stunt, like Chaplin’s gear-worming in Modern Times more than a decade later, is so bound up in the shared anxieties of modern living that it can only function as a necessary comic release. The skyscraper and the clock aren’t incidental: They are central symbols of a society just settling into an industrialized, urbanized modernity. Lloyd’s sight gag not only taps into the feelings of the period, but fully and succinctly articulates them…Miscommunication and physical blunders abound in a metropolis seemingly designed to not only accommodate, but actively encourage both, and if Lloyd happens to walk unknowingly into one disaster after another, it’s less the fault of his own clumsiness than the unsound landscape he’s resigned to traverse.”

Safety Last! further seems to preach the merits of adapting quickly to your environment, thinking fast on your feet, and following a “fake it ‘till you make it” philosophy. Despite the numerous impediments and setbacks he faces, the boy learns to rapidly and intrepidly use surrounding resources to his advantage – from passing cars that transport him to work to coat hooks that hide him from the landlord to scissors he employs Solomon-like to settle an argument between two customers to a flagpole that helps him escape an angry dog.

Perhaps the film’s greatest gift to viewers, besides generating copious quantities of laughs and gasps from viewers, is its significance as a cherished evergreen work from the silent filmmaking era. Containing the most iconic and remembered visual from any silent screen film – a man dangling from a gigantic timepiece – affords Safety Last! the stature of silent cinema exemplar and ambassador of a vintage form of filmmaking that deserves recognition and appreciation in the 21st century. What better way to introduce to younger generations the charms and craftsmanship imbued in pre-talking pictures than to perpetuate this imagery and recommend a viewing of Safety Last!? When your movie has the most instantly recognizable shot of a film made more than 100 years ago, it carries a special significance and has the power to keep the low-tech, practical effects magic of silent movies alive for new audiences.

In the same way that Gen Y and Z have embraced the retro charms and aural intimacy of vinyl, perhaps Safety Last! can increasingly be appreciated for its old-school thrills and prescient preoccupation with the hurried pace of the modern world made all the more chaotic and stressful by technology. And if its visuals can continue to be evoked and echoed in future years, we can hope that Safety Last!, whenever it is referenced in pop culture, serves as a crucial gateway drug to other pre-sound masterworks crafted by Chaplin, Keaton, Griffith, Lang, Murnau, Eisenstein, Dreyer, Lumière, von Sternberg, Vergov, and their ilk.

To hear a recording of our CineVerse group discussion of this film, conducted last year, click here; to listen to our current Cineversary podcast episode on Safety Last!, click here.

Safety Last! deserves to be celebrated a century not just because it’s a timeless laugher with a higher ratio of yuks per minute than any silent film or classic movie ever made. It also features the most instantly recognizable image in silent films: a bespectacled man hanging from a clock face 12 stories above the ground. The ubiquity and – no pun intended – the timelessness of this image underscores how important and beloved this film remains in pop culture. As proof of how pervasive this iconography is, recall the CoverGirl Outlast TV commercial from 10 years ago featuring actress Sophia Vergara hanging from a giant clock face that resembles the one in Safety Last!

The events and incredible stunts appear and feel real, largely because the movie was shot on location outdoors in Los Angeles using actual buildings and featuring non-acting crowds that arrived to watch. It also looks authentic because Harold Lloyd and a human fly stuntman actually scaled that building, with a circus performer used for the foot-hanging-from-a-rope scene. Lloyd and these performers took significant risks and jeopardized their lives to make the action appear as genuine as possible. Bear in mind that the filmmakers don’t use special effects like matte paintings or rear screen projection. Lloyd’s stunt work is all the more remarkable considering that he lost a thumb and index finger on one of his hands a few years earlier.

Additionally, the picture goes non-stop without any slowdown or weak scenes and is chock full of great jokes and gags—the finest and most extended of which is the scaling of the building—but there are gags within gags and climaxes within climaxes that layer the film with comedy and thrills. Amazingly, however, this 73-minute film only has about 10 scenes. The cinematography here is advanced for a 1923 comedy. Safety Last!, especially in its last half hour, benefits from the use of varying camera angles – including POV shots – and recurrent movement of the camera.

Despite its reputation as one of the greatest and funniest silent comedies, arguably, Safety Last is more entertaining and fulfilling as an action thriller than a comedy. Some film historians and scholars credit Safety Last as the progenitor of a particular genre. “The structure of Safety Last!...is instantly recognizable to the modern viewer,” wrote Criterion Collection essayist Ed Park. “It’s still the template for the contemporary action flick, in which the story sets up a spectacular chase or fight sequence at the end.”

Interestingly, although the film is remembered for its outdoor climbing sequences and close calls, the movie’s first half primarily takes place indoors while outside scenes dominate the second half.

Lloyd, unlike Charles Chaplin and Buster Keaton, benefited from an everyman look and quality as well as his rounded spectacles, which gave him a more intelligent yet fallible appearance. Lloyd is billed as “the boy,” but his employee card clearly lists him as “Harold Lloyd.” Chaplin had The Little Tramp, and Lloyd had this character, often referred to as “Glasses.” Lloyd said in interviews: “Someone with glasses is generally thought to be studious and an erudite person to a degree, a kind of person who doesn’t fight or engage in violence, but I did, so my glasses belied my appearance. The audience could put me in a situation with that in mind, but I could be just the opposite of what was supposed…In the pictures that I did, I could be an introvert, a little weakling, and another could be an extrovert, the sophisticate, the hypochondriac. They looked alike in appearance, with the glasses, which I guess you’d call a typical American boy.”

Like Keaton, Lloyd’s characters also used improvisational resourcefulness to ingeniously get out of jambs. For instance, in Safety Last, he and his roommate hang hilariously beneath coats on hooks from the landlady, he crawls beside a box to get away from the floorwalker, and when he falls he immediately does push-ups to save face.

Chaplin infused more sentimentality, emotionality, and pathos into his characters and situations and typically portrayed a more lonely and solitary figure in The Little Tramp. Keaton leaned more heavily on getting laughs and incorporating slapstick and stunts in his pictures and often maintained a stoic, deadpan expression. Like Keaton, Lloyd often employed impressive and inventive stunt work and physical comedy and embodied everyman characters at odds with an increasingly chaotic world; in fact, several of Keaton’s films echo shots, gags, and stories from Lloyd’s works and vice versa. However, Lloyd preferred to play more optimistic, enthusiastic, likable, all-American types who commonly struggle to keep pace with a hectic contemporary world.

Speculating on how Chaplin or Keaton might have approached this film, DVD Savant Glenn Erickson posited: “Charlie Chaplin would turn tail and run, or blunder into the problem wearing a blindfold and find out only later how much danger he was in. Keaton would envision the crisis as a series of fantastic mechanical challenges, relying on the 'harmonious chaos' of physical reality to save his skin. Harold's extended building climb is a crazy gauntlet of dangers and accidents within accidents…Harold may be crazy but he never gives up. He's got the right stuff to (literally) reach the top.”

Longtime collaborator Hal Roach remarked of his friend: “Harold Lloyd worked for me because he could play a comedian. He was not a comedian. He was the best actor I ever saw being a comedian . . . No one worked harder than he did.”

Fascinatingly, Lloyd made more films and money than Chaplin and Keaton combined in their prime years. Roger Ebert wrote: “I could understand why Lloyd outgrossed Chaplin and Keaton in the 1920s: Not because he was funnier or more poignant, but because he was merely mortal and their characters were from another plane of existence. Lloyd is a real man climbing a building; Keaton, as he stands just exactly where a building will not crush him, is an instrument of cosmic fate. And Chaplin is a visitor to our universe from the one that exists in his mind… Perhaps that is what makes him special: (Lloyd) is determined to be a great silent comedian, and succeeds by experimentation, courage, and will. His films are about his triumph over their making.”

Perhaps a case can be made that certain later films by Chaplin and Keaton, including The General, Steamboat Bill, Jr., The General, and Modern Times, were partially inspired by Safety Last! Possibly the ascent of the Empire State Building in King Kong 10 years later took a cue from this movie, as did the first Die Hard film, in which John McClane must traverse the various stories of a skyscraper in superhuman fashion. Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol features Tom Cruise performing extraordinary stunts along the side of a Dubai skyscraper, and the documentary Man on Wire details a gripping tightrope walk between The Twin Towers – two movies that instantly bring Safety Last! to mind. And films that pay homage to Safety Last! include Stanley Kramer’s It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, The Jackie Chan martial arts comedy Project A, the first Back to the Future film, The Hudsucker Proxy, and Martin Scorsese’s Hugo.

While it’s not a thematically rich film, subtexts are present in Safety Last! if you want to look for them. One is good and bad timing: The boy is pressured to arrive at work on time, and frequently it appears that time is not on his side, yet an actual clock face serves as a lifeline and he continually has the benefit of fortuitous timing. Ponder, as well, all the visual nods to time: the clock face, his body swinging like a pendulum, and the work time clock. From the start, we are told in an intertitle: “The boy was always early.”

The economic and practical challenges of surviving and coping in an increasingly industrialized metropolis are other takeaways. From public transportation that can’t accommodate him to throngs of angry customers seeking service in a busy department store, the boy is faced with one obstacle after another. In his review for Slant Magazine, Calum Marsh commented: “Lloyd’s clock-stopping stunt, like Chaplin’s gear-worming in Modern Times more than a decade later, is so bound up in the shared anxieties of modern living that it can only function as a necessary comic release. The skyscraper and the clock aren’t incidental: They are central symbols of a society just settling into an industrialized, urbanized modernity. Lloyd’s sight gag not only taps into the feelings of the period, but fully and succinctly articulates them…Miscommunication and physical blunders abound in a metropolis seemingly designed to not only accommodate, but actively encourage both, and if Lloyd happens to walk unknowingly into one disaster after another, it’s less the fault of his own clumsiness than the unsound landscape he’s resigned to traverse.”

Safety Last! further seems to preach the merits of adapting quickly to your environment, thinking fast on your feet, and following a “fake it ‘till you make it” philosophy. Despite the numerous impediments and setbacks he faces, the boy learns to rapidly and intrepidly use surrounding resources to his advantage – from passing cars that transport him to work to coat hooks that hide him from the landlord to scissors he employs Solomon-like to settle an argument between two customers to a flagpole that helps him escape an angry dog.

Perhaps the film’s greatest gift to viewers, besides generating copious quantities of laughs and gasps from viewers, is its significance as a cherished evergreen work from the silent filmmaking era. Containing the most iconic and remembered visual from any silent screen film – a man dangling from a gigantic timepiece – affords Safety Last! the stature of silent cinema exemplar and ambassador of a vintage form of filmmaking that deserves recognition and appreciation in the 21st century. What better way to introduce to younger generations the charms and craftsmanship imbued in pre-talking pictures than to perpetuate this imagery and recommend a viewing of Safety Last!? When your movie has the most instantly recognizable shot of a film made more than 100 years ago, it carries a special significance and has the power to keep the low-tech, practical effects magic of silent movies alive for new audiences.

In the same way that Gen Y and Z have embraced the retro charms and aural intimacy of vinyl, perhaps Safety Last! can increasingly be appreciated for its old-school thrills and prescient preoccupation with the hurried pace of the modern world made all the more chaotic and stressful by technology. And if its visuals can continue to be evoked and echoed in future years, we can hope that Safety Last!, whenever it is referenced in pop culture, serves as a crucial gateway drug to other pre-sound masterworks crafted by Chaplin, Keaton, Griffith, Lang, Murnau, Eisenstein, Dreyer, Lumière, von Sternberg, Vergov, and their ilk.